The New York Times headline that splashed across our devices three weeks ago screamed The Pandemic Erased Two Decades of Progress in Math and Reading. It’s time for American educators to scream back.

Did the pandemic erase two decades of progress? No. Did it harm our youth in a myriad of ways? Yes. But the data that prompted the screaming headlines don’t capture the harm. They capture the results of a national sample of nine-year-olds on a standardized test. Once again, a snapshot from an isolated instrument is used to make a broad statement about systems and individuals, neither of which it can remotely encapsulate. The broken state of education in our nation goes much deeper than a standardized test can possibly depict, just as the learning potential of the student taking that test is so much more than it can possibly portray.

I have been an educator since the day I knew what one was—from the tiny schoolroom my parents let me create in our spare bedroom to teach my animate and inanimate pupils (aka my brother, my grandmother, and my stuffed animals) to a wide variety of classrooms over the past thirty years, ranging from a rural high school in North Carolina to an inner city junior high in Florida to a graduate classroom in Michigan to an alternative high school in northern Virginia. I have taught online, in people’s homes, in church classrooms, and on my living room couch. I have worked with AP students who earned perfect scores on the SAT and students who have “no measurable IQ.” The study and practice of education has been my life’s work.

And that headline makes me want to scream.

The alarm sounded by the “nation’s report card” will be received as the educational equivalent of a six-alarm fire to which all available personnel should respond. But if the response is federal policies crafted by polarized politicians to pour funding and programs onto the fires of our educational system that will be deemed successful when the standardized test scores of nine-year-olds rise from the ashes and show that pandemic losses have been regained, nothing will have changed.

American educators, it is time for us to scream back at the headlines. If you interact with a child in our nation, you ARE an American educator. Our global, interconnected, fast-paced world is the classroom of our nation’s youth, and the most educationally valuable moments of a child’s day are any in which he or she is engaged in everyday life with another human being. Our children’s education IS in crisis, but the problems are much bigger than a standardized test can possibly capture. Our youth live technology-saturated lives and face unbelievable risks of violence, addiction, and abuse. Our teachers have an innate passion for teaching and a love of young people but have been shackled for years by standards, tests, policies, and paperwork. Parents are overwhelmed, overworked, and under-supported in their day-to-day lives. And our leaders are embroiled in an unbelievable national display of pervasive, ego-driven polarization in which everyone loses.

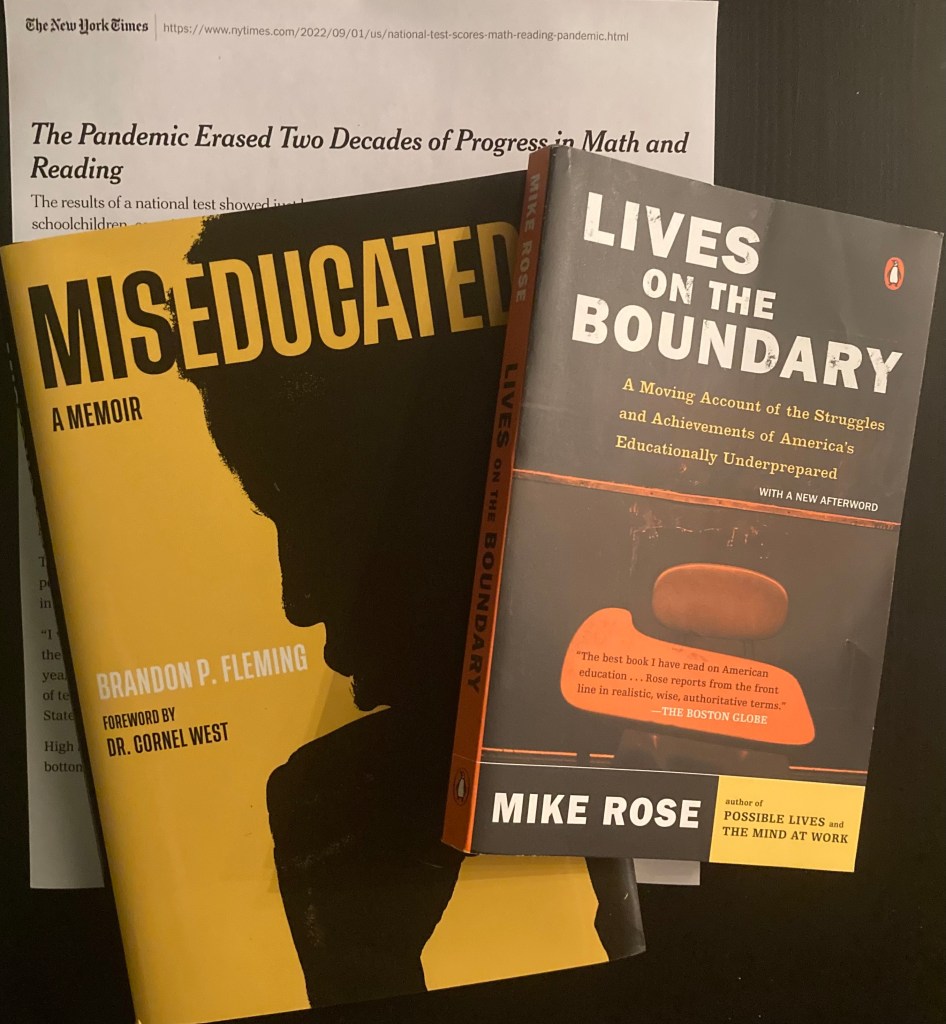

Almost thirty years ago as an eager graduate student in the University of Michigan’s School of Education, I devoured the words of Mike Rose in his autobiography Lives on the Boundary. As Rose reflected, his story “makes particular and palpable the feeling of struggling in school, of not getting it, of feeling out of place” but also conveys “an overall narrative of possibility, possibility actualized through one’s own perseverance and wit, yes, but also through certain kinds of instruction and assumptions about cognition, through meaningful relationships with adults, through a particular set of understandings about learning and the relationship of learning to one’s circumstances” (p. 247). His work guided and inspired my classrooms for years to follow.

A few weeks ago as I drove to visit my father, I was equally mesmerized by the voice of Brandon P. Fleming as he narrated his memoir Miseducated. Fleming’s story is remarkable and profound and inspiring. It simultaneously encapsulates the despair and the hope of what education is and what it can be. His vision and his commitment to act on that vision dramatically changed the lives of numerous young people and their families—not to mention his own. In the epilogue of his memoir, Fleming implored his scholars to use the voice he helped them discover to break barriers and shift balances of power. Fleming reflected that “where a man has no voice, he does not exist. He can even be present and not exist, because inferiority is an induced consciousness whose physical manifestation begins with silence. He is seen, but he is not heard. He is not understood. Because he does not matter…But when he discovers his voice, he determines that he can sing and summon the sound of hope” (p. 251). By singing his own song, Fleming inspired me to sing mine.

Rose and Fleming, two men who lived in very different times and cultures affirmed the same truth I captured in my dissertation written this past year—a study based on the theories of Reuven Feuerstein that captured the powerful mediation of mothers homeschooling learners with special educational needs and disabilities. It is the truth that beats in the heart of every educator and must be the central tenet for any person or program that hopes to facilitate true learning. That truth is the belief that every single individual has something to offer and the potential to learn and grow—EVERY individual—from the nonverbal, non-ambulatory son of one of my dear friends to the high school student with the perfect SAT score to the adolescent gang member in the prison cell awaiting trial as an adult to the little girl with the “immeasurable IQ” who wakes up in my house every morning eager to learn. To learn and grow and discover what they have to offer, they need people to see them, love them, invest in them, and equip them. They need their basic needs met. They need to feel safe. They need assessments that measure their learning propensity and education that is tailored for them, not standardized education geared toward standardized testing of standardized “learning.”

The alarm has sounded on a national crisis in education that is not two years but many decades in the making. Its solutions will not be found in polarized, politicized, bureaucratized systems but in the individualized education of unique students with unique needs. It will take place in homes, classrooms, fields, studios, workplaces, and communities across the nation. It won’t look the same for every child because no child is the same as another. It will require innovations like those of educators like Rose and Fleming and the mothers who shared their stories with me. Most critically, it will demand trust—not in politicians or policies but in people—traditional and nontraditional teachers—and the young people they are inspired to teach. It will require advocacy and a willingness to listen. It will require leaders to set aside egos and personal agendas and provide what is needed to make a difference in individual lives and communities. It will require teachers, students, and parents to “sing their song” and to listen to the song of others. Some of those songs will be beautiful and inspiring; others will be tragic and painful to hear. We will learn from them all and if we act, lives will change—one at a time—and with them, our nation.

American educators, it’s time to scream back.