I do not recall attending church as a child, though I think we may have gone occasionally on holidays. My first memories of church are from 5th grade when a neighbor invited me to the Wednesday night program at her Baptist church that was within walking distance of our neighborhood. I began attending on Sunday mornings and was baptized in that church at age 13. I went on local mission weeks and to church camps with the youth group and eventually branched out to attend Fellowship of Christian Athletes (FCA) programs in my first two years of high school.

Church was not a part of my later high school and early college life until I began dating the man I would eventually marry. Not having grown up in church, my faith roots were shallow and my knowledge was limited. When he invited me to his church, I went eagerly, not realizing that the Mormon church was not simply another denomination but an entire entity (cult) unto itself. The experience of immersing myself, joining, and eventually insisting on my own excommunication from the Latter Day Saint (LDS) church (it is the only way out), left me burned by religion and subsequently agnostic.

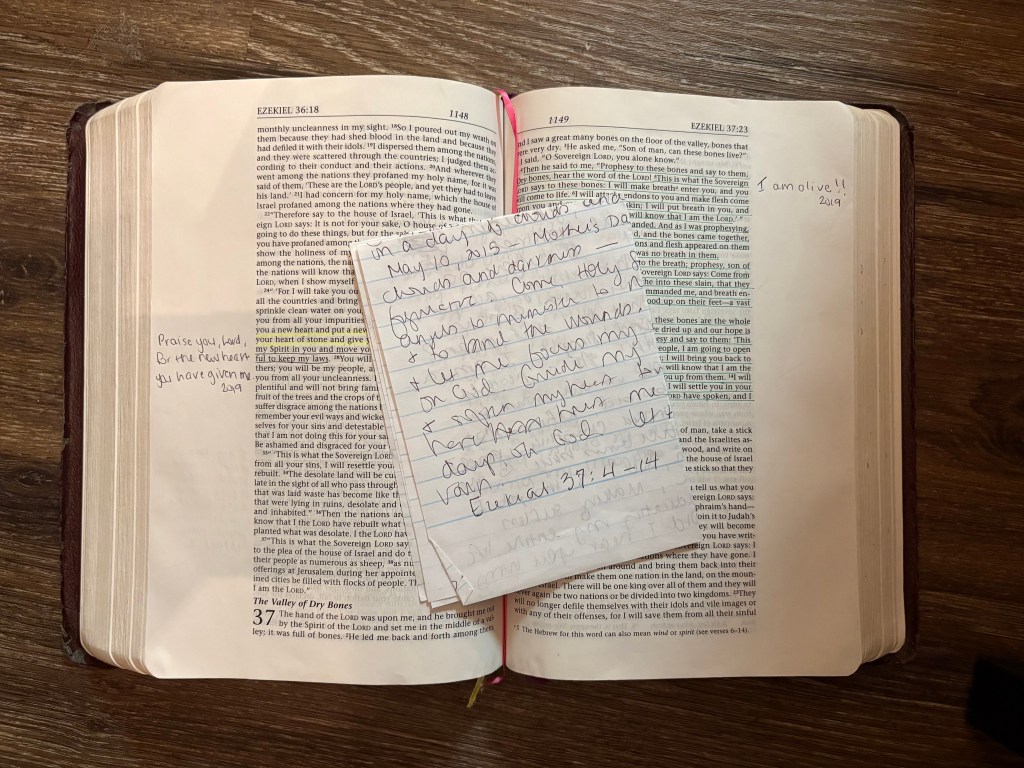

Only love for my unborn first child and a desire for her to have the spiritual roots I had lacked propelled me back into a church five years later, and I went determined to be physically present but spiritually distant. Two churches and an incredible pastor later, the mustard seed of faith planted in my teenage years sprouted. As a military spouse, I experienced multiple churches in the years that followed, and each nurtured my faith in its own imperfect ways. Everywhere I lived, the church was central to my life. The church has been the primary place where I worshipped, studied, fellowshipped, learned, led, served, and grew for going on thirty years.

I believe in the church. I love the church. I am who I am because of the church. The church has always been flawed and broken and at times has fallen grossly on the wrong side of history. Unfortunately, this is one of those times for the church in America (the only context I have experienced and can speak personally about). The people in our nation and those influenced by it are in desperate need of justice, but the church as an institution is too sick to be a force for change. It, in fact, is both overtly and covertly complicit in numerous acts of injustice in our nation and abroad. We are not without hope, however, for the church as Christ presented and empowered her can and should speak into the injustice we are experiencing and inflicting.

I do not claim to be a church historian or an expert on the church as an organization. I am confident that there are individual churches and perhaps even entire denominations that are relatively healthy. I am currently a part of one such church community. However, as an entity, the organized church in America has become consumed by the empire that houses it, which renders it ineffective as a force that opposes the injustices inflicted by that empire. I could reflect upon numerous examples related to poverty, race, gender, sexual orientation, immigration, and more, but as a culmination of a summer spent studying the Israel-Palestine conflict, I will limit my reflections to the church’s impotence as a force of justice and change in the genocide and ethnic cleansing that is ongoing in Gaza.

As I have shared previously, I had extremely limited knowledge of the Israel-Palestine conflict prior to taking a course at St. Stephen’s University this past summer. The message I had received from the evangelical non-denominational church I left last fall after seven years of membership and full participation was simple: Israel was the good guy that any true Christian would defend at all costs. Palestinians were terrorists and indefensible. Any alternative opinion was heresy.

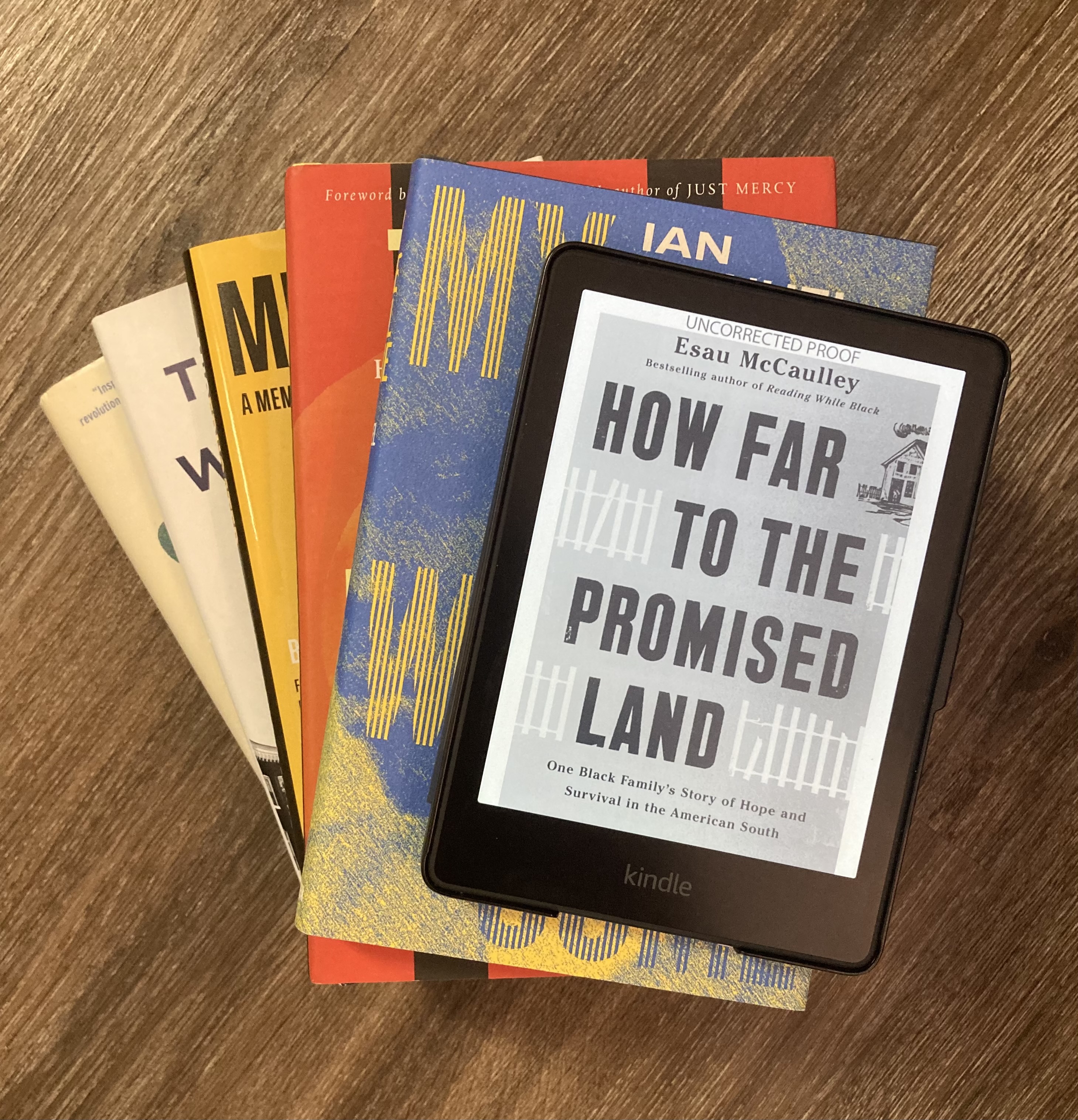

Interestingly, none of this messaging came to me via direct instruction or even explicit teaching from the pulpit. It was just understood and soaked into me through prayer requests, prophetic words shared on Sunday mornings, and the corporate response to news related to Israel and Palestine, especially the October 2023 attacks. I have always been an eager student—taking classes, attending Bible studies, and reading books recommended by pastors and others I respect—but in no church that I have attended over the past thirty years was I ever encouraged to read or understand anything related to Israel-Palestine. I credit Dr. Munther Isaac’s December 2023 sermon “Christ in the Rubble” with sparking my curiosity enough to eventually lead me to the SSU course.

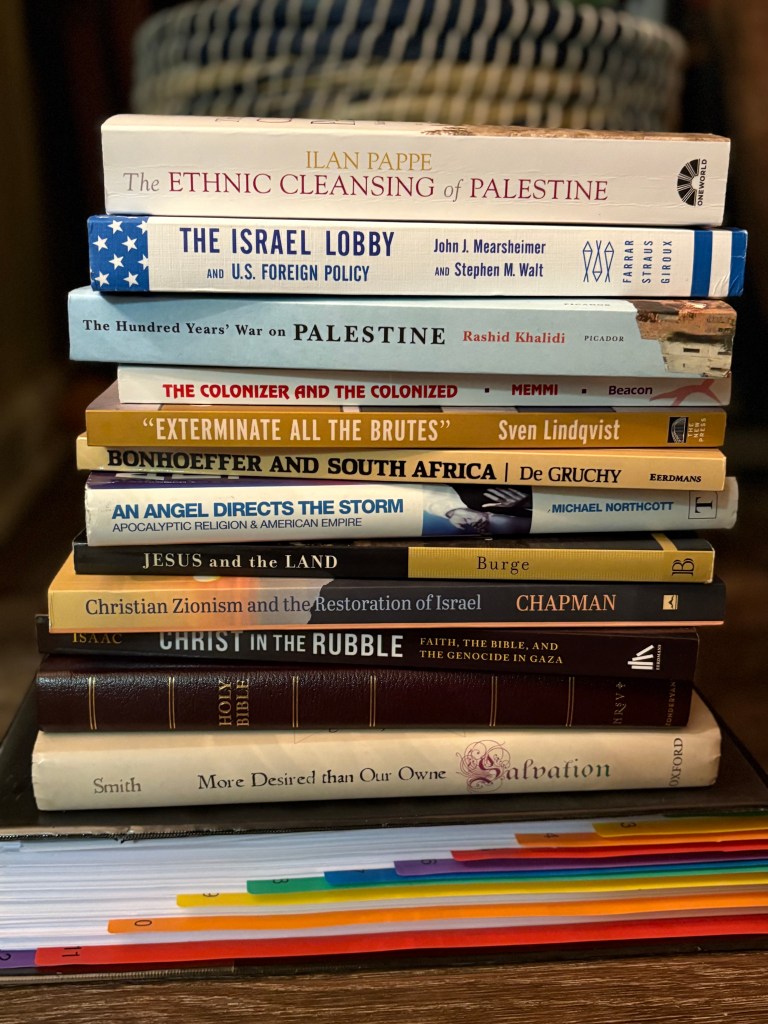

Week after week this summer, we read and discussed colonialism, Zionism, land, empire, eschatology, theology, antisemitism, and Kairos. Week after week, we asked ourselves, “What can we do?” Week after week we confessed to one another our churches’ silence and our own paralysis within our church bodies. Why?

America is no longer just a nation. She is an empire. She is also a civil religion. Much of the American church has believed a false narrative that America was founded as a Christian nation, that she is chosen. It has traded worship of Jesus for worship of country and a mandate that Jesus never issued. It has allowed flawed theology to seep into its teaching and has prostituted itself to political movements under the guise of numerous “moral imperatives.” Meanwhile, it has become its own consumer-driven, results-oriented, bureaucratic entity that is so cumbersome even at the local, individual level that congregations or pastors who may glimpse or even know in their hearts that they are off-course are powerless to effect change. Much of the church has crawled in bed with empire, most especially the current U.S. administration, and is slapping Christian labels onto policies, actions, and statements that reflect nothing of Christ, tarnishing His name in horrific ways.

With each topic we studied this summer, the picture of the American church’s direct endorsement of the ethnic cleansing and genocide in Palestine grew clearer. It is not just a matter of complicity. It is worse than that. The American church and the empire housing it have directed, funded, enabled, defended, and covered up atrocious crimes against humanity. And for the reasons just described, it is not equipped to be a force of justice or change.

Thankfully, the American church is not the church. The church—the ekklesia—was built by Jesus and is indestructible (Matthew 16:18). It consists of members of the body of Christ that Paul describes in 1 Corinthians 12. It is not bound by geographical location, by biological traits, by cultural norms, by denominational guidelines, by political affiliation, or any other man-made label or construct. Christ is its head and He has uniquely gifted, called, and equipped each member of the body “for the work of ministry, for building up the body of Christ, until all of us come to the unity of the faith and of the knowledge of the Son of God, to maturity, to the measure of the full stature of Christ” (Ephesians 4:12-13). Paul implored the church in Ephesus that the members of the body of Christ “must no longer be children, tossed to and fro and blown about by every wind of doctrine, by people’s trickery, by their craftiness in deceitful scheming. But speaking the truth in love, we must grow up in every way into him who is the head, into Christ” (Ephesians 4:14-15). The same applies to the church today. If the members of the body of Christ are to grow up into Him, we need to reflect His teachings such as those in the Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 5-7) and the Sermon on the Plain (Luke 6) and His numerous parables about who is our neighbor and how often we forgive and how we are to treat the foreigner, the outcast, and the least of these.

The organized church in America is too entangled in empire and its own bureaucracy to function as a force of change in any of the injustices that plague our nation or the world, especially related to Israel-Palestine. The hope is in the individual members of the body of Christ whose head is Jesus, who lived and died and was raised from the dead and seated at God’s “right hand in the heavenly places, far above all rule and authority and power and dominion, and above every name that is named, not only in this age but also in the age to come” (Ephesians 1:20-21). God has “put all things under his feet and has made him the head over all things for the church, which is his body, the fullness of him who fills all in all” (Ephesians 1:22-23).

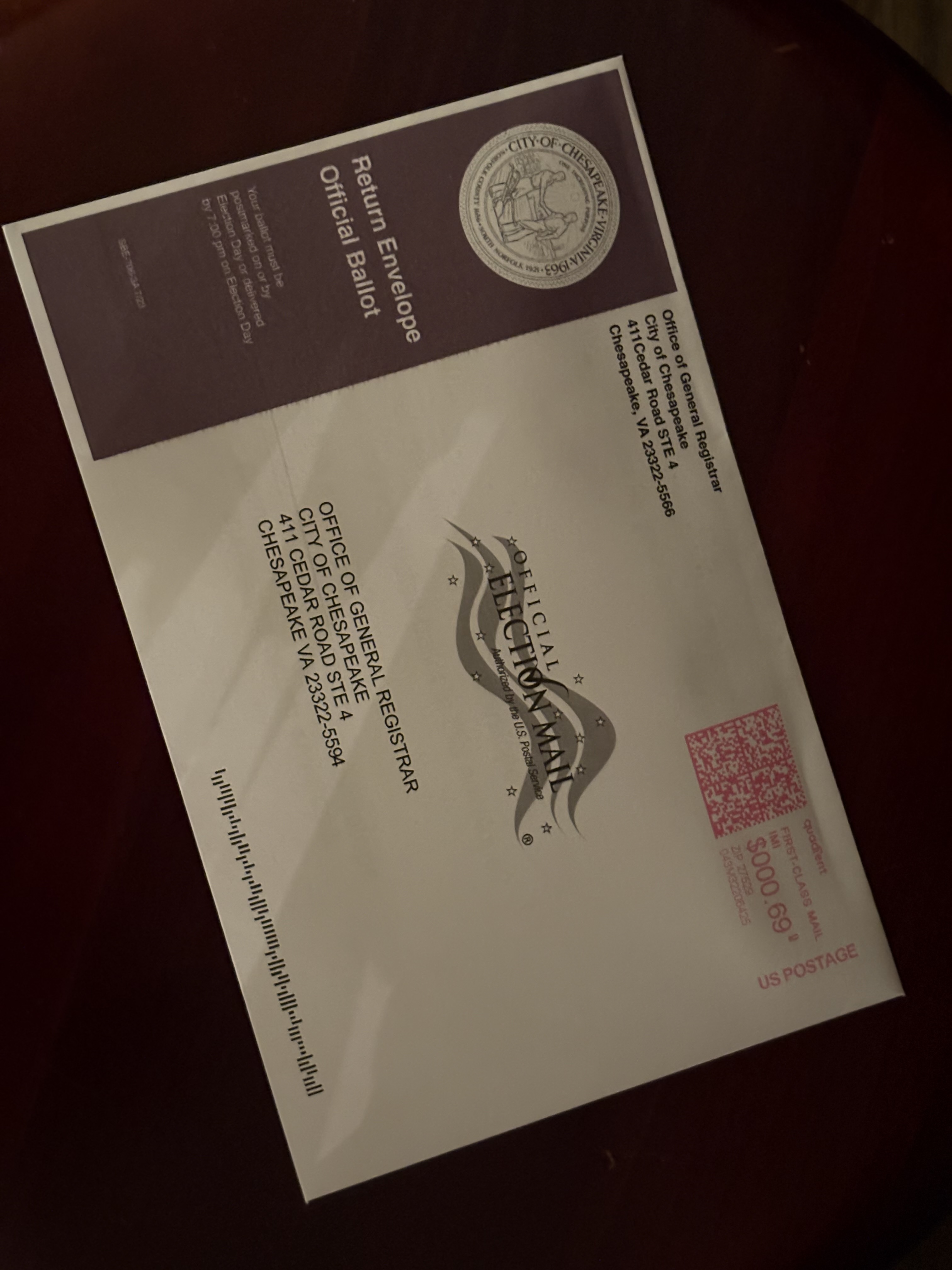

As individual members of the body of Christ, we must centralize His teachings and apply them to the injustices of our day. We must use our voices, our hands, our feet, and our minds to speak and act and teach and write and utilize our gifts in His service. In doing so, we will be a force of change in our communities, our schools, our workplaces, our congregations, our denominations, and our government. But we must not be motivated by a desire to convert or overpower the empire or to wed it to the church. As my pastor, Brian Zahnd, has said, “Empire gonna empire. But don’t confuse it with the kingdom of Jesus.”[1] We are not citizens of the empire but “citizens with the saints and also members of the household of God, built upon the foundation of the apostles and prophets, with Christ Jesus himself as the cornerstone. In him the whole structure is joined together and grows into a holy temple in the Lord; in whom [we] also are built together spiritually into a dwelling place of God” (Ephesians 2:19-22). His Kingdom has come and is yet coming. Until its fulfillment, we are His body in our nation and our world, including in homeless encampments, at the border, in prisons, across the aisle, in our neighborhood, and—imperatively—in the rubble of the tragedy that is occurring in Palestine and in Israel.

[1] Facebook post (June 22, 2025)