I had a meeting this spring with an engaging, intelligent young woman who is doing some of the most meaningful work I can imagine for some of the most overlooked people in our local community. We shared experiences, passions, and ideas for how I can contribute to the work of the non-profit organization she serves. We discussed writing, research, teaching, and storytelling and how I can use them to make a difference. Toward the end of the meeting, she said words like these to me: “I can see that at your very core—at the heart of it all—you are a mother. When you write about or share your experiences, you are mothering all of us who read or hear them.”

It was one of those life-giving, truth-telling moments that you know you will always remember because something inside you shifts and your view is forever changed. Her words affirmed one of the central lessons of my last seven years that had been percolating in me but that I had not previously been able to articulate: After two decades of believing that my mother-self and my other-self were in conflict, I have finally realized that we are one.

I graduated this spring. Well, technically, I graduated last August, but the ceremony was in May. The timing and expense of the ceremony made it a bit challenging so I chose not to attend and didn’t give it much thought once the decision was made, until…

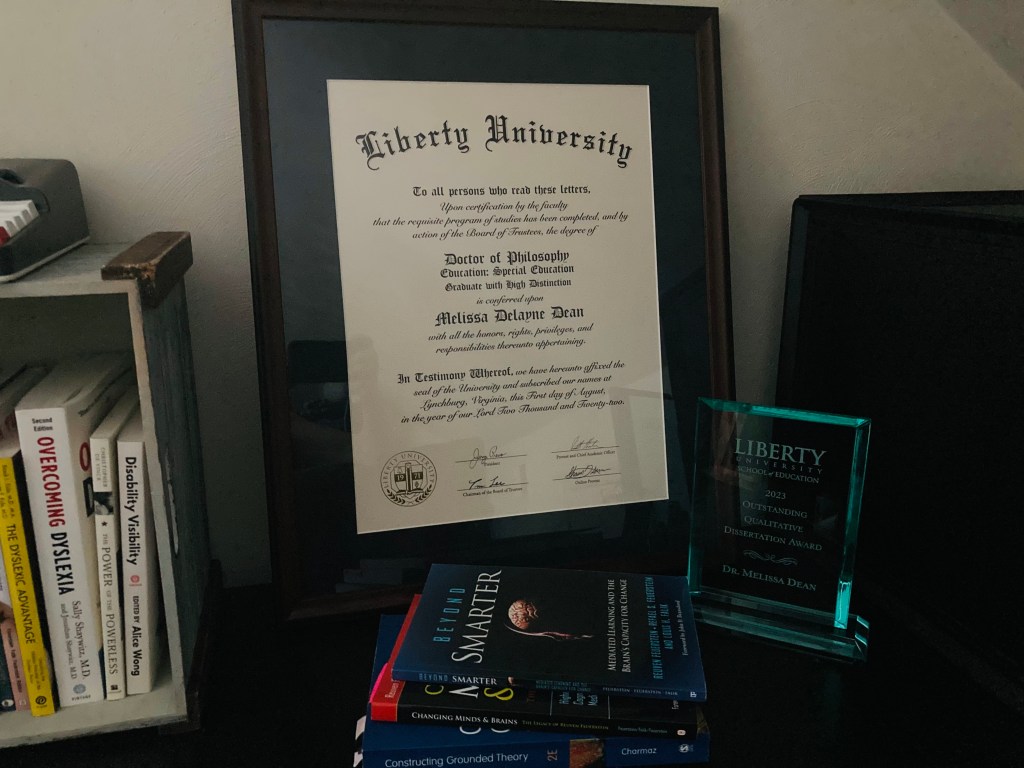

Shortly after 10 on the Thursday morning of my commissioning ceremony, as I was running errands and about to drive to a haircut appointment, I received an unexpected text from my dissertation chair: “Melissa!!! You just won the qualitative dissertation award!!!!!!” I was stunned. And honored. And a little sad that I wasn’t there to receive it in person. But as the day went on and I shared the news with my family and processed it a bit more, the significance began to register. This was more than just an unexpected accolade to me; it was an external affirmation of a series of choices I had made over the years I spent pursuing that degree…a journey that ended far differently than it began.

I have always valued education. My mom encouraged it in every way, and my dad frequently told me that there were two things in life that no one could take away from me—my education and my self-respect—so I knew it would be wise to have as much as possible of both. Attending college wasn’t a decision I made but an assumption I lived out. And as a lifelong Tar Heel basketball fan, the choice of school was as well.

Two years after graduating from college and getting married, the military sent my husband to the University of Michigan for a grad school tour. After a four-year long-distance relationship/engagement and two-years of ship deployments, it sounded heavenly to attend grad school together, so I applied to get my master’s degree in English Education at the same time. Surprised by a research assistantship opportunity that I literally stumbled upon in the U-M School of Education women’s bathroom within a week of our move to Ann Arbor, the doors opened for me to pursue basically all the education I wanted while serving in that RA role. By the next spring, I had completed the master’s degree I had originally sought, so the professor I worked with highly encouraged to enter Michigan’s Ph.D. program. The project we were working on had enough data to fuel numerous dissertations, making the opportunity especially appealing. As much as I wanted to apply, I knew my husband would be transferred to Washington, D.C. for a payback tour as soon as he graduated the following spring. It is impossible to complete a Ph.D. in a year and virtual learning did not exist in 1995, so starting the degree and finishing it from afar would have been nearly impossible. I didn’t want a second master’s degree, so I petitioned the Dean to allow me to pursue U-M’s defunct Educational Specialist (Ed.S.) degree, which was basically the coursework of a Ph.D. that culminated in a major paper approved by a committee but not a dissertation based on original research.

I learned I was pregnant with our first child just weeks after beginning that degree, so I chose to transition from being a research assistant, which required a good bit of travel, to being a teaching assistant. Pregnancy and the Ed.S. coursework coexisted nicely. Even writing the draft of my Ed.S. paper was manageable. My daughter arrived the day after her due date (and my birthday)—six weeks before the end of the semester, her dad’s and my graduation ceremonies, and our move to DC. I couldn’t afford to miss a class and still finish on time, so I took my postpartum donut to class with me, nursed her in my little grad student office between classes, and sat on the floor of my chair’s office calming my colicky baby while discussing the paper revisions necessary to appease the requests of my other committee members. I recall one of the members suggesting I take an incomplete and finish the paper over the summer, but I knew that would never happen. Those weeks were a blur of exhaustion, crying, leaking milk, healing, and doggedly staying the course. Somehow, I finished.

I joked later that I promptly hung both graduate degrees over my daughter’s changing table. As a military spouse, I was at the mercy of my husband’s career demands. Over the subsequent twenty years, I pursued as much work as I could manage—teaching night school, writing for newspapers, editing, and eventually designing courses and teaching online—with promises that “my turn would come.” I hoped to finish that Ph.D. someday and teach at a university and perhaps one day become an author. That day always got pushed into the future…after this, after that…until eventually I couldn’t see it anymore.

Twenty-five years after graduating from U-M, I began applying to doctoral programs while taking the necessary steps to move into a home on my own. To those who don’t know me well, this seemed foolish, but to those who do, it made all the sense in the world. Reading, writing, books, words, ideas, discussions, learning…are what make my heart sing. They are how I process the world. My therapist asked how I would manage the workload with all of the stress and responsibility that was now upon me as a single parent. “School is therapy to me,” I told her, and it truly was.

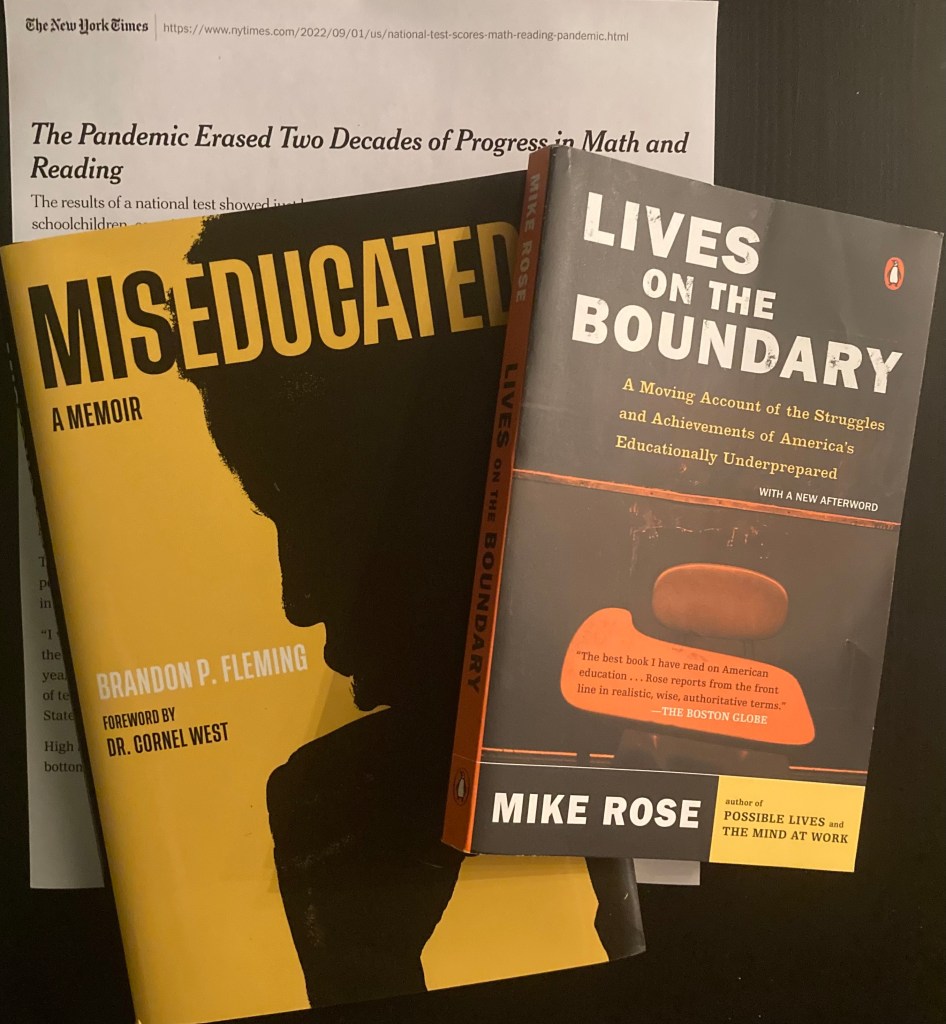

I assumed my Ph.D. should be in English Education or Curriculum Development, the two fields I had previously studied and acquired the most experience in during my patchwork career. A year into English coursework, however, an external battle prompted me to change direction. I had homeschooled our children for fifteen years with the full support of my spouse, but suddenly that choice was under attack. I made a phone call that changed everything.

In my conversation with the head of Liberty’s Special Education department, I inquired about the logistics of switching my degree program, knowing that having a terminal degree in the field would end any future conversation about my capacity to homeschool children with special needs. What I didn’t realize at the time was that I was also marrying my professional and parenting lives in a way that would benefit me and the children for years to come. I was also forming a relationship with an incredible professor who would become my mentor and eventually my dissertation chair.

The journey from that conversation to last year was both challenging and invigorating. I loved being a student of a field that so directly affected my own children, and I was exposed to theories that completely revolutionized my views of education, teaching, parenting, and the potential of all learners. Completing my coursework and entering the dissertation stage was simultaneously exhilarating and terrifying. Choosing a topic, however, was simple for me. I knew that even though it would attract no attention in my field, I wanted to study families who chose to homeschool learners with special educational needs and disabilities—families just like mine.

The dissertation road is never smooth—approval delays, finding participants, interviewing, transcribing, and coding are all part of an arduous and very non-linear journey, much of which is completely out of the researcher’s control. I had hoped to graduate in the spring of 2022 but that extended into summer. My dad had been diagnosed with cancer and expressed his desire to see me graduate before he lost the battle he faced. On a mission to grant his desire, I resigned myself to the idea that “done is better than perfect.” But when I started to analyze the data and write Chapters 4 and 5, I quickly realized that I couldn’t tell my participants’ stories any other way than with the justice they deserved. My participants were me, their children were my children, and their voices deserved to be heard.

I submitted my final draft, defended in July 2022, and technically graduated that August. Even though I wasn’t there to receive it, learning that of all the qualitative dissertations submitted in Liberty’s Education Department for the 2022-2023 school year, mine was chosen for distinction overwhelmed me with gratitude, not so much for the award but for the affirmation of all the little choices that led to it: the choice to postpone the degree for over two decades; the choice to homeschool; the choice to adopt children with special needs; the choice to enter a new field at the highest level during a time of such intense personal stress and transition; the choice to study a low-profile, marginalized population that means the world to me but offers no professional currency; and the choice to finish strong instead of just finishing.

Outsiders may not realize how remarkable it is for a dissertation about homeschooling learners with special educational needs and disabilities written by a single mom over fifty to be recognized but I know, and it overwhelms me with gratitude and affirmation. I could not have produced that research and its resulting model apart from the choices I made and the experiences I had in the years that have passed since I drove away from Ann Arbor, Michigan in 1996, leaving so much behind.

So now my degree hangs in my guest room office where I work at odd hours of the day and night for a local non-profit doing what I expect to be incredibly meaningful work in service of things that truly matter to me. My primary job is and will continue to be that of mother and teacher to my kids, but I now see how inseparable that is from everything I am and how much better it makes me at anything I choose to do. My mother-self and my other-self are truly one, and I finally realize—and celebrate—the value of that marriage.