Our homeschool co-op shared a bittersweet final day of the year yesterday. It was our first year at Kindred Homeschool Collective. We joined Kindred because it is inclusive and focuses on seeing the image of God in all people, valuing everyone’s story, and loving like Jesus. We have witnessed all of these things and more over the course of the year and while a summer break will be nice, we look forward to returning in August.

Despite the joy we have all experienced participating at Kindred, it was a challenging year for me. Inclusive doesn’t always mean accessible, and the co-op meets in a beautiful but historic church that posed a lot of challenges for Tess and those of us caring for her.

The morning before our last day, I received an unexpected message from our friend Rosean, the youth pastor at our co-op’s host church, who also serves as our co-op security person (and so much more). From the very first day of classes, he recognized our challenges and went out of his way to help Tess navigate the stairs, going so far as to meet us at the car most weeks. He always had an encouraging word and a smile to share and never once made us feel like a burden. It was a gift. But when he sent me photos of a new ramp he had installed over the steps that Tess needed to navigate the most each school day, I was so overcome with emotion that I had to sit down.

I had just had a conversation the previous week with one of our co-op board members about my concerns for managing the next school year, knowing I will likely have less resources and assistance to help Tess and Lydia during the times I will be teaching and serving in the co-op. Any parent in a truly collaborative co-op (as opposed to a drop-off program) faces challenges juggling their own family’s needs with their responsibilities to teach and serve, but when your child is fully dependent on assistance to navigate her environment and meet basic care needs, there are extra struggles. This ramp was an act of seeing and empowering Tess while letting me know that I am not alone in my struggle to manage a positive but often challenging day.

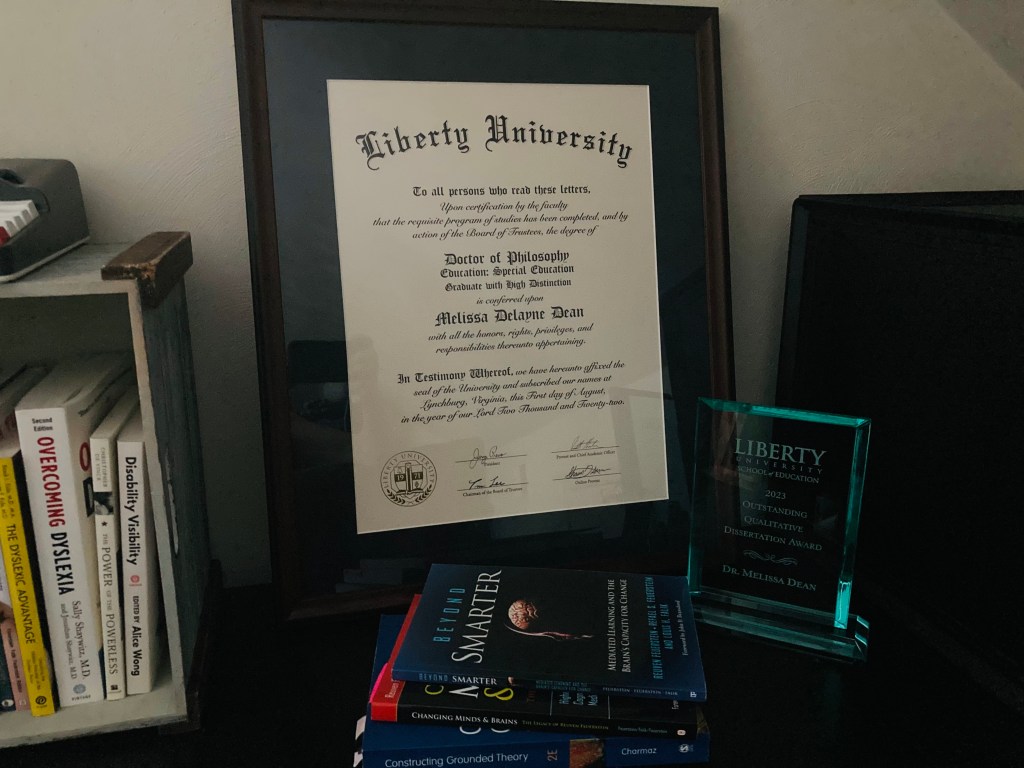

Vision is often enhanced through contrast and this experience helped solidify a decision with which I have been wrestling for the past few months. I shared in a previous post that I was excited to be starting a Princeton Theological Seminary (PTS) graduate program in Theology that focuses that focuses on Justice and Public Life. In that post, I also shared that there were portions of the program I was not sure how I would fulfill but that I was trusting God to make a way. Soon after sharing my decision to commit to the program, I learned that Tess needed her sixth cerebral shunt revision. This one was planned, while the others have been emergent; however, each one has reminded me of the unpredictability of my life as a single mom to kids with medical challenges. While I do believe in trusting God to make a way, I also believe in exploring options and planning ahead. That process led me to realize that the PTS program was not accessible to me.

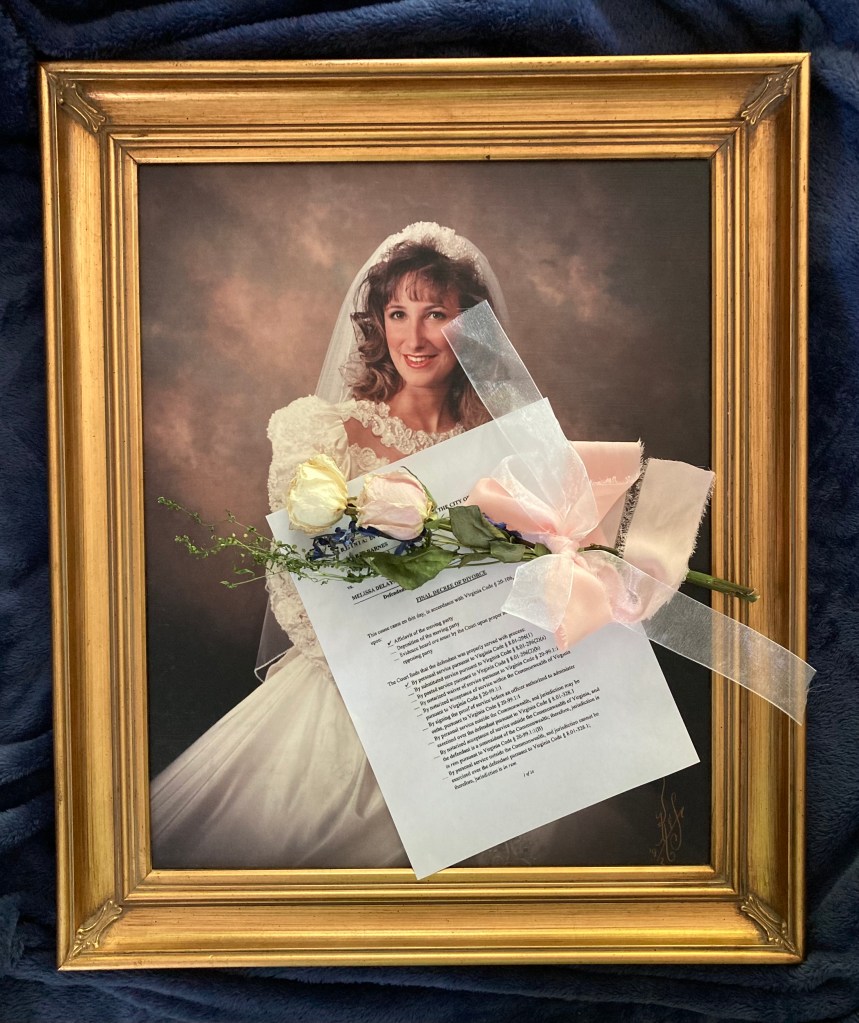

I have thought a lot about accessibility and inclusion for my kids but have recently come to realize that parents of kids with disabilities need inclusion and accessibility too. We live in a constant state of alert, balancing the needs of a typical child or young adult with the often complex needs that come with our kids’ unique challenges. The basic things like an unexpected trip to the store can be complicated, and we live on the precipice of emergency. Very few, if any, people can step into our life, even on an extremely temporary basis, which limits our mobility, reliability, and especially, our control. Our “no” is often an “I wish” or “If only…,” and our “yes” is always a “hopefully.” It’s a beautiful but complex life that both expands and restricts us. We wouldn’t want a different life and most definitely not a different child, but the world rarely sees or understands our internal or external struggles. Our focus is on securing accessibility and inclusion for our kids but truthfully, we need both as well.

One of my favorite things “hobbies” for most of my life has been following North Carolina Tar Heel basketball. In basketball, players often use their pivot foot to create space against a defender. If I am trying to make a play on the basket and I lift the ball over my head, the defender can fill the void and hinder my movement. If I hold the ball directly in front of me, it is likely to be knocked away. My best option is to use my pivot foot, step forward, and sweep through to back my defender up, creating space for myself to move in a new direction and make a play on the basket.

I could have remained in the PTS program and hoped for the “act of God” that would be necessary for me to fulfill the program component that is just not conducive with my primary responsibilities, but if that act never came, I would not complete the degree. Instead, I decided to pivot and survey the court for other options. And the vision I gained from that pivot showed me more options than I had known of last summer when I first discovered PTS’s program. One of them quickly emerged as ideal.

Next week I will begin classes toward my Master of Ministry (MMin) degree in Theology and Culture (with an emphasis on Justice) at St. Stephen’s University. I am beyond excited! It would take another post to share all the many ways St. Stephen’s is perfect for me. In short, their mission perfectly aligns with my own:

“The Mission of St. Stephen’s University is to prepare people, through academic, personal, and spiritual development, for a life of justice, beauty, and compassion, enabling a humble, creative engagement with their world.”

And equally valuable—even essential—to me, SSU is inclusive and made itself accessible to me as a single parent of kids with exceptional needs. From my first inquiry to the creation of an outlined course of study that provides me with options for a variety of scenarios that may occur in this beautiful but often out-of-my-control life, they sought to understand my situation on more than a surface level and responded to it, not just with sympathy or even empathy but with action. I cannot describe the peace that accompanied that for me. Now instead of beginning a program with a cloud of uncertainty hovering above me, I begin from a firm, supportive foundation that frees me to be focused and enthusiastic!

Looking back, I see God directing me toward SSU all along in small, subtle ways that I could not have seen if I continued to cling to the ball of PTS’s program or raise it up high to keep someone from taking it from me. I would have either lost the ball or had obstructed vision and movement. Instead, I was able to pivot and open space for myself to do something better than what I originally planned. In the process, I learned that inclusion and accessibility matter for me, too, and that just as I do for my kids, I need to advocate for that and surround myself with the people and communities who see and empower me to do so.

I’m sitting in a coffee shop in a sketchy section of Orlando, Florida, a couple of miles from the law school where AMCA Moot Court Nationals will be held in a few hours, seriously questioning my priorities. Sunny day, zippy rental car, no kids—and I am going to spend the day watching moot court rounds inside a law school?!? And I’m excited about this?!? I literally passed the exits for Disney World, Sea World, AND Universal Studios to get here!?!

I’m sitting in a coffee shop in a sketchy section of Orlando, Florida, a couple of miles from the law school where AMCA Moot Court Nationals will be held in a few hours, seriously questioning my priorities. Sunny day, zippy rental car, no kids—and I am going to spend the day watching moot court rounds inside a law school?!? And I’m excited about this?!? I literally passed the exits for Disney World, Sea World, AND Universal Studios to get here!?!