Diamonds form below the Earth’s surface in molten rock under specific amounts of extreme heat and pressure. Their resulting molecular structure makes them the hardest known mineral in the world, so a diamond can only be scratched by another diamond. In their natural state, however, diamonds are rough stones that require processing to become a sparkling, gift-worthy gem. The task of crafting that gem falls to a diamond cutter.

Many choices go into the diamond cutter’s work: whether to cut the stone to a manageable size by cleaving it along its weakest plane, by sawing it with a rotating blade, or by utilizing a laser. Whichever method is chosen, the process is time-consuming and demands that the diamond cutter decide which part of the diamond will become the table (the flat top with the largest surface area) and which will become the girdle (the outside rim at the greatest point of diameter). The cutter then uses other diamonds to hand cut the diamond to the desired shape and to create the girdle’s rough finish. Finally, he or she uses a wheel and an abrasive diamond powder to smooth the diamond and create a finished look.

Last week marked the tenth anniversary of this blog, a platform I created to capture our infant twins’ adoption story as it unfolded, but which ultimately became a space to reflect upon and share a variety of stories over this past decade of life. In the end, not only have the experiences I captured transformed me, but the process of reflecting on and writing them has as well. My hope in sharing them is always that perhaps each one touches and, in some small way, transforms at least one of the people who take the time to read them.

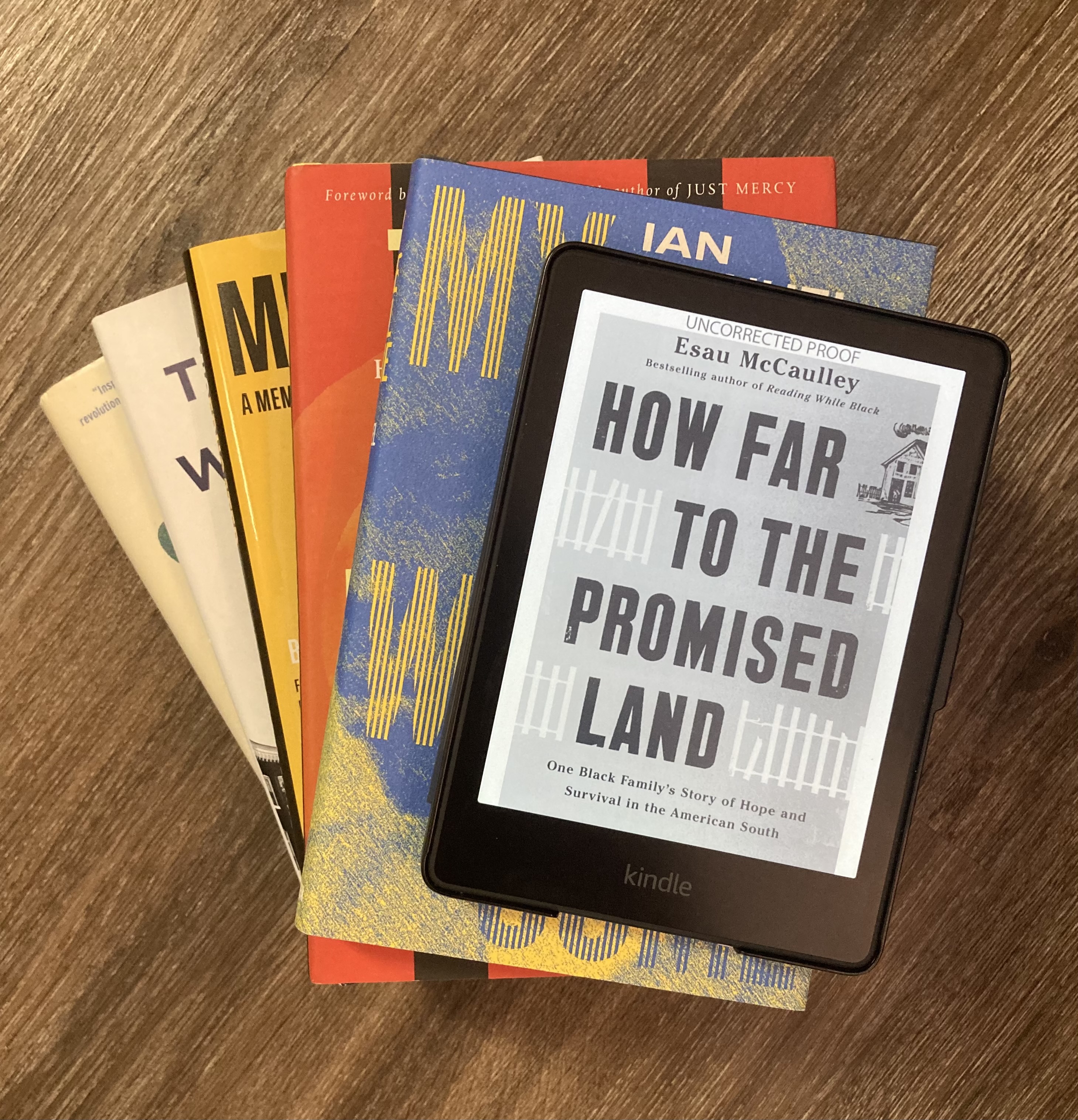

As I reflected on this milestone in my own writing journey this past week, I also had the privilege of participating in a Q&A Session with Esau McCaulley about his forthcoming book How Far to the Promised Land: One Black Family’s Story of Hope and Survival in the American South. Listening to Esau share the decisions he made about what to include and not include in his book, I was struck by the similarities between the craft of memoir writing and the craft of diamond cutting.

Like a diamond cutter, an author who writes of his or her personal journey begins with a vast amount of naturally-occurring raw material. Each person, event, and experience in a writer’s life is a part of his or her quarry of stones. How does a memoir writer even know where to begin?

Diamonds are one of three forms of carbon, which is both “one of the most common elements in the world and is one of the four essentials for the existence of life.” Just as the raw material of a diamond is brought to the surface and transformed by a diamond cutter into something exquisite, so are the events of a life in the hands of an author. The choices made during that extensive process affect the value of the gem produced.

I eagerly pre-ordered Esau’s book last winter when the release date was first announced, and when the invitation was later extended to join his launch team, I quickly responded. Esau has long been one of the most respected voices to which I turn for a thoughtful, biblically-sound response to the issues of social and racial justice that pervade our nation. I knew Esau as a young seminary graduate where he served in a church our family attended immediately after our move to Virginia. His wife Mandy was our children’s primary care physician during her three-year pediatric residency at the naval hospital near our home.

Because of my respect for Esau as a writer and theologian, the snippets of knowledge I had from social media of his family’s experiences after leaving Virginia, and my love for memoir as a literary genre, I anticipated an enjoyable and engaging read. What I experienced, however, was so much more.

I have written previously of the power of story and have made a personal vow to follow the advice that Farah Jasmine Griffin’s father gave her to “read until you understand.” In an effort to understand as much about the experience of others as I can possibly grasp, I have read memoirs by Anthony Ray Hinton, Jr., Wes Moore, Viktor Frankl, Frederick Douglass, Michelle Obama, Brandon P. Fleming, Alicia Appleman-Jurman, Harriet Jacobs, Ian Manuel, Elie Wiesel, Michelle Kuo, and many others. Each has profoundly affected me in its own way; however, Esau uniquely crafted his memoir in ways that provided me new and deeper levels of understanding and reflection.

Diamonds are judged on four factors that determine their beauty. The first factor is the cut, which is determined by the cutting process described above and the resulting facets and shape of the finished diamond. A diamond’s clarity is a measurement of its flaws or inclusions. Its weight is measured in carats, and its color ranges from yellow to icy white, which is the most transparent and most expensive. In addition, a diamond’s luster and dispersion of light, though not one of the four factors, also contribute to its beauty and worth.

As the diamond cutter of his story, Esau’s choice of cut laid the foundation for the entire book. Rather than the more common, narrow focus typical of most memoir (and powerful in its own right), Esau had a pivotal experience that helped him see the need to write about “the community and family that shaped me—the people normally written out of such stories—and how the struggle in each life to find meaning and purpose, regardless of its outcome, has a chance to teach us what it means to be human.” He wrote his story along with that of his mother, his father, his grandparents, and numerous other family and community members in what is ultimately a wider yet deeper picture of his own life and especially the interconnectedness of all lives.

In crafting his story, Esau digressed from the work of a traditional diamond cutter who would seek to minimize flaws and inclusions for the sake of clarity. A diamond may be more valuable the closer it is to perfection, but clarity in a powerful story is achieved through the transparent inclusion of the underside of life—the parts that we often hide but actually need to examine, to understand, and sometimes to act upon. Esau took the risk of sharing some incredibly difficult and flawed aspects of the people of whom he wrote, including himself, and in doing so provided a powerful opportunity for his readers to both understand and be understood. I could not list the number of connection points offered in the twelve chapters of this book, but I would dare to say that I believe its story will resonate in some way with anyone who reads it.

The weight of Esau’s story is significant. As the story of a black family in the American South, how can it be anything but heavy? As I write this, news has broken of a racially-targeted mass shooting in Jacksonville, Florida—a place that both my family and the McCaulleys have called home. We need this story and many others like it. We need a nation that encourages reading and discussing these stories. Most of all, we need the transformation and action that can come from understanding the intricacies of people, especially those who are targeted in crimes such as the one in Jacksonville—and yes, even those who commit them.

Esau observed, in the chapter on his marriage, that his own marriage and more broadly, any interracial marriage, “is not about racial reconciliation in America; that is too much weight for anyone to bear.” The same could be said about this memoir. It is a weighty story of one family over a period of specific times and places. It cannot carry the burden or promise of solving the issues it brings to light, but it can offer to take each reader a step closer on his or her journey of understanding. As someone who has been deliberately pursuing her own understanding, I received from Esau’s diamond crafting an entirely a new vantage point from which to see, not only an individual but, “the story of a people.” And as the subtitle of the book states, it is both a survival story AND a story of incredible hope. Reading it evoked a full range of emotions in me from sorrow to laughter, from outrage to respect. I laughed, I cried, I raged, I learned, and ultimately, I was transformed a degree more by the experience.

The most expensive diamond is transparent. Writing this memoir had to be costly for Esau and his family, but the result is a multifaceted, brilliant gem with immense value to the reader. Part of the power of his narrative is that while it offers redemptive hope and forgiveness, it acknowledges the cost of trauma…the message that is often avoided yet most needed in areas of any type of reconciliation, whether racial, social, or personal. His story not only moved me closer to understanding, it gave me a new vantage point from which to see and understand ALL stories, including my own. It encouraged me as a writer to continue crafting my own diamonds out of the molten rock of my own experiences and to do so with thoughtful intention to the cut, the inclusions, and the clarity with which I share.

The dispersion of light is not considered one of the four main factors on which a diamond’s beauty is judged. Dispersion occurs when white light passes through a prism and splits into its spectrum of colors—what we know as the colors of the rainbow. The very best stories are those that can be held up and examined so that the light hits them in a myriad of ways from multiple angles and perspectives. That light reveals truth about the subjects of the stories, their authors, and those who hear them. But in a truly powerful story, that light will be dispersed and the story will transform all who encounter it—the writer, the reader, and the world in which they live—perhaps even such that white light is seen for the spectrum of color it truly is.

Write on, diamond cutters.

(Information on diamond cutting retrieved from How Stuff Works.)