I never knew what to do with Israel-Palestine. For years, mostly in church, I heard outrage toward Palestinians, unconditional loyalty toward Israel, and biblical justification for both. My attempts to understand the issue were meager, and I concluded that I had no opinion on the matter because it was just too complicated to understand.

The events of October 7, 2023 changed that—but not immediately. Because it was a Saturday, I learned of the attacks at church on Sunday morning. An elder led the congregation in prayer for Israel. I was appropriately sorry but didn’t think much about it because…well, it was just too complicated.

Three months later, I heard a sermon by Christian Palestinian pastor and theologian Dr. Munther Isaac called “Christ in the Rubble.” In my Evangelical Christian bubble, Palestinians were terrorists, not Christian pastors. Listening to his sermon grieved me and left me with a myriad of questions, but I did not pursue them because they still seemed…well, too complicated.

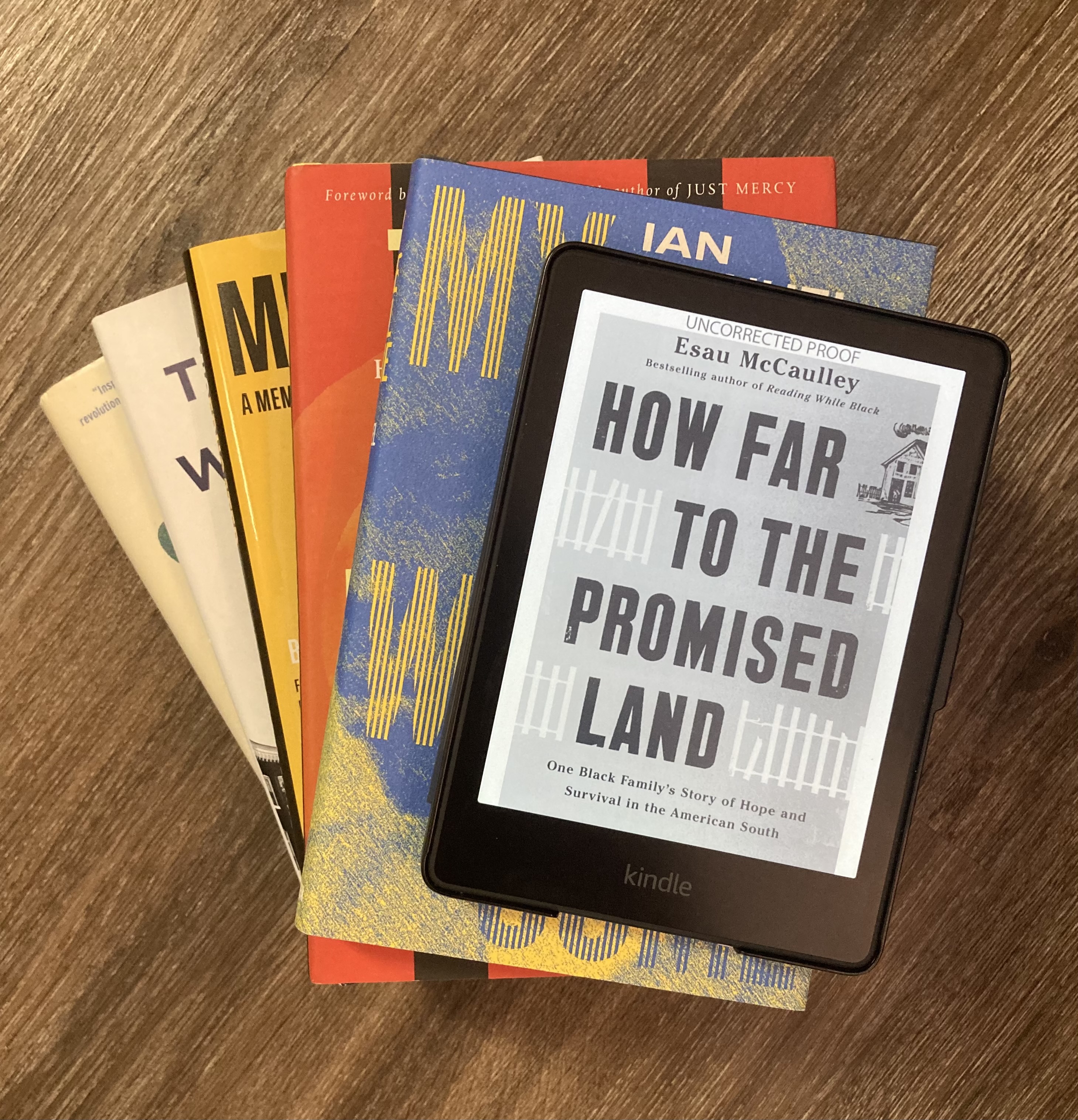

A year and a half later and several months after a series of revelations led me away from my evangelical church home, I received a copy of Dr. Isaac’s book, also called Christ in the Rubble, for my birthday. Within the first few chapters, I was mesmerized. Page after page, Dr. Isaac measuredly described the historical events that led to what I eventually realized has become a story of ethnic cleansing and genocide. His book is monumental because it takes something complex and emotionally volatile and makes it understandable for someone like me who was not encouraged or motivated to learn about, and had assumed she could not understand, the issues surrounding Israel-Palestine.

Two months later, as part of my M.Min. program at St. Stephen’s University, I had the opportunity to enroll in a summer course called “Zionism, the Church’s Colonial Legacy, and the Palestinian Call.” Part of me was nervous. This would be my first SSU course and the topic was something I had only a book and a sermon’s worth of knowledge about. Would I be able to engage meaningfully? Would the learning curve be too steep? The other part of me was excited. I entered SSU to challenge myself to stretch my faith in world-changing ways, and I now knew that this is a watershed event of my lifetime. With my evangelical bubble burst, I could not—would not—live as an ignorant puppet. I wanted to understand—truly understand—and see the issue with the eyes of Jesus.

Dr. Mark Braverman proved to be as knowledgeable and gentle a guide as Dr. Isaac. In his own words, he is “a Jew, deeply connected to my tradition and to my people, who is horrified and heartbroken over what is being done in my name: for the suffering of my Palestinian sisters and brothers in Palestine and in exile, for the psychological and spiritual peril of my own people who have imprisoned themselves behind the wall they have built.”[1]

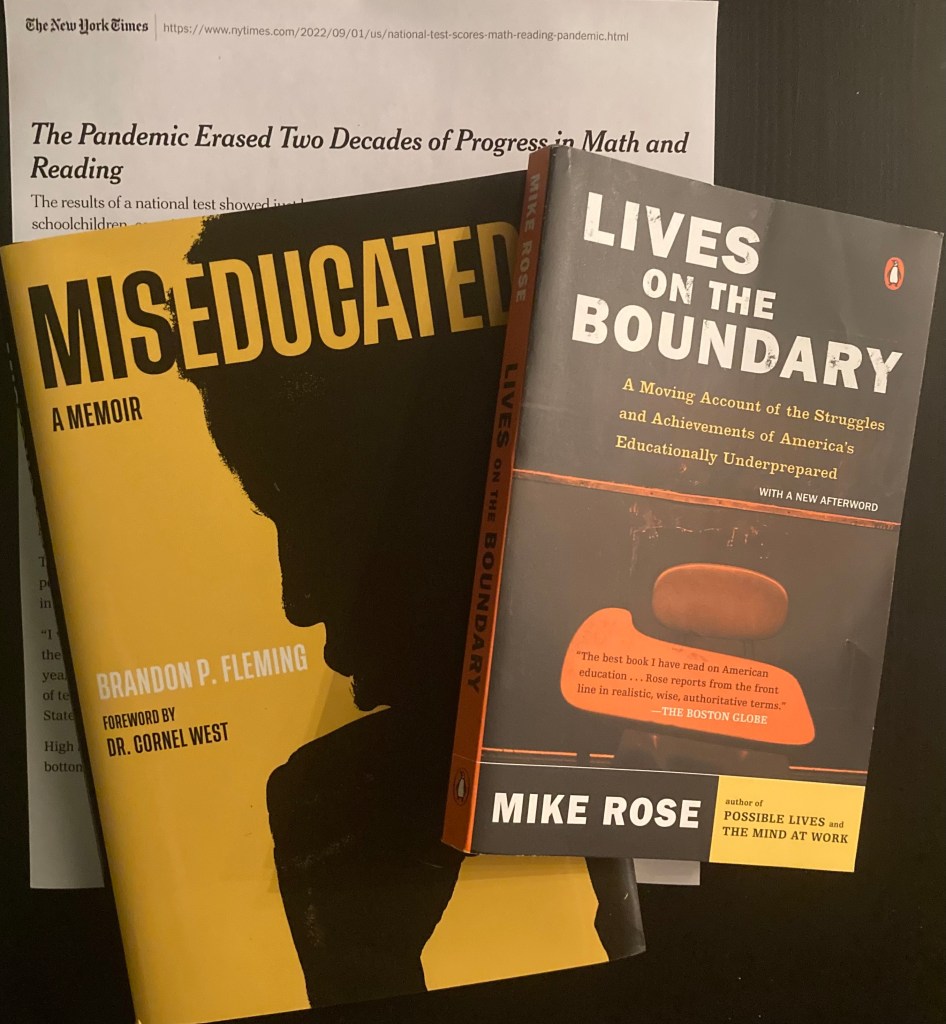

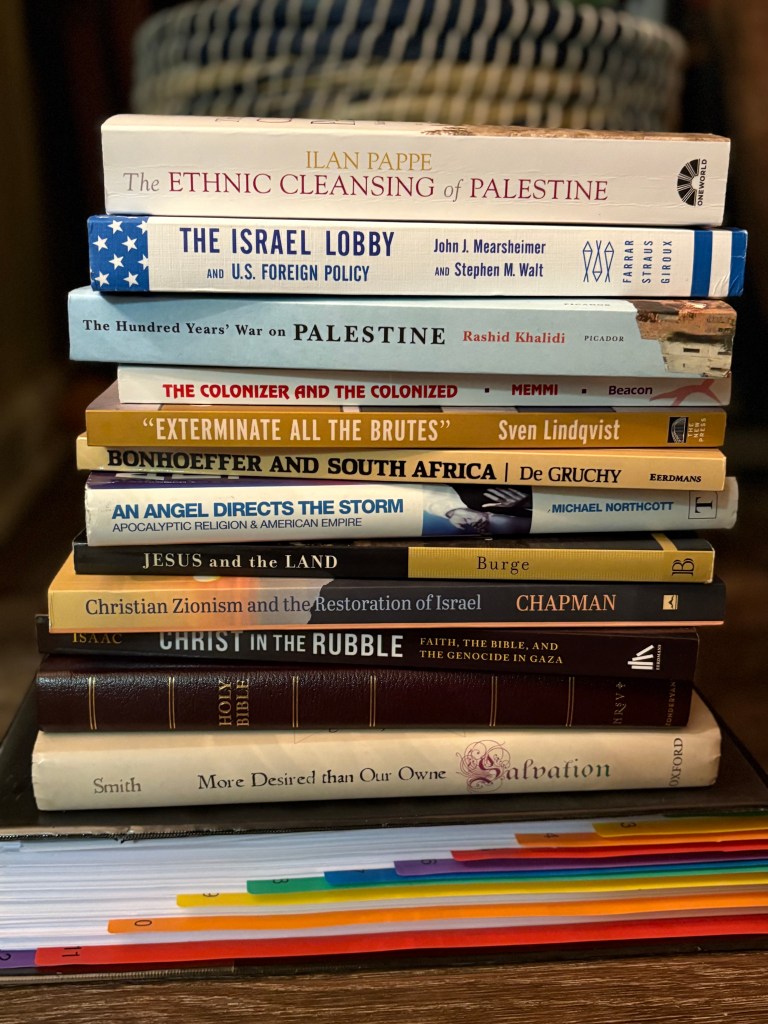

Over twelve weeks, I read broadly and deeply a high volume of texts from numerous scholars and theologians. I grew to realize that what we are witnessing is simple: Israel is undoubtedly committing ethnic cleansing and genocide against the Palestinian people. The reasons are more complex but identifiable. They include but are not limited to colonialism, Zionism, the Israel Lobby, flawed theology about the promise of land, false narratives about the founding of America, scripturally unsupported eschatology, and a twisting of the concept of antisemitism. At the root of most of these reasons lies a beast called empire.

Silence is complicity. And thankfully, there are numerous examples of nations, faith communities, and individuals who have spoken out. Choose a few Kairos documents to read and you will find hope and a way forward amid an overwhelming tragic situation. There are options from South Africa, the United Kingdom, the United States, the Philippines and most importantly, Palestine itself. More recently, you will find formal declarations of apartheid and genocide, including admissions from Israeli sources.

As a youth and young adult, I read numerous memoirs from the Holocaust and always wondered why no one stopped the horrors from occurring. I told myself that they would have had they known. Well, today we know. The world knows. Reports of ethnic cleansing and genocide reach us daily. And yet, the cries continue, the people starve or are killed trying not to, the bombs fall, and the war machine keeps humming along.

In my class, multiple students raised the point that they could not speak of what we were learning in their churches. I thought about that in context of my own experience. I have been active in church bodies in multiple states over the past thirty years, but in no church that I have attended was I ever encouraged to read or understand anything related to Israel-Palestine. Despite this, I knew the drill: Israel was the good guy that any true Christian would defend at all costs. Palestinians were terrorists and indefensible. Any alternative opinion was heresy.

Interestingly, none of this messaging came to me via direct instruction or even explicit teaching from the pulpit. It was just understood and soaked into me through prayer requests, prophetic words shared on Sunday mornings, and the corporate response to news related to Israel and Palestine, especially the October 2023 attacks. I have always been an eager student—taking classes, attending Bible studies, and reading books recommended by pastors and others I respect—but only in the past six months, under a pastor faithful to Jesus rather than wed to Christian nationalism or Christian Zionism or the evangelical church agenda and as a student at St. Stephen’s University, a Canadian school whose mission is “to prepare people, through academic, personal, and spiritual development, for a life of justice, beauty, and compassion, enabling a humble, creative engagement with their world,” have I been encouraged and equipped to learn about the Israel-Palestine conflict and to form my own opinions about what I have learned.

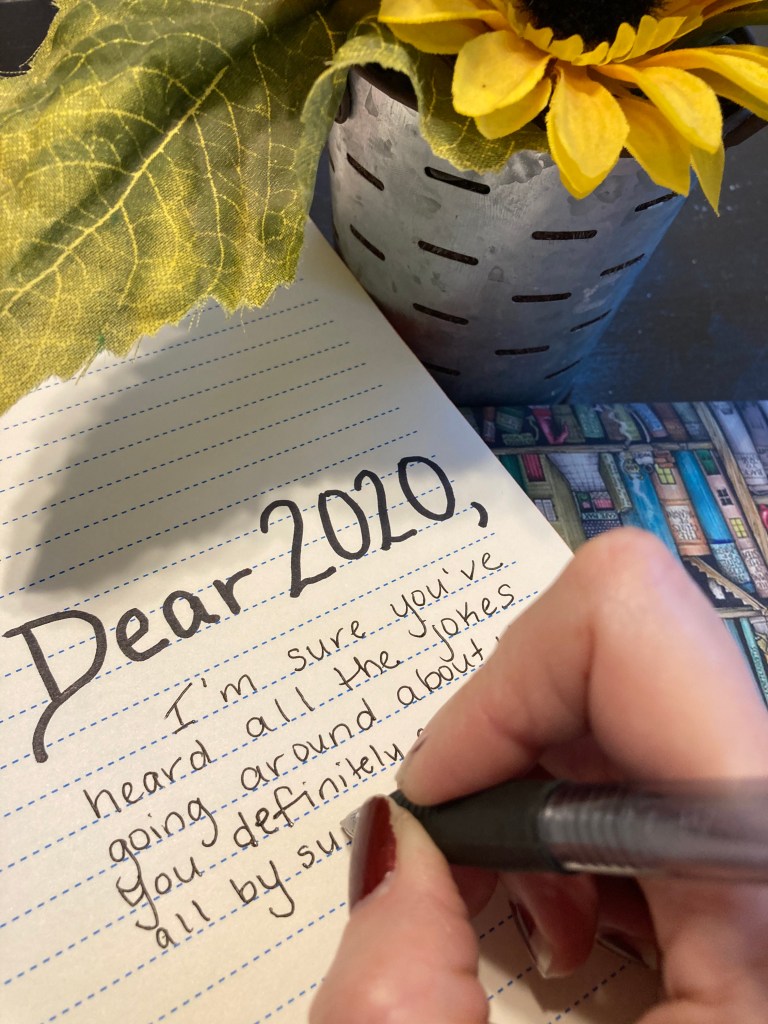

This is my Kairos moment, my time to speak out, to cease being complicit, to become a force of change, to use my voice and my gifts as a writer and teacher and encourager in my very small corner of the world. My message is simple: It isn’t complicated, and it is utterly critical.

“But for those children who live and die in affliction tonight, are we not obligated by our humanity (if not our faith) to stop switching the channel, to at least attend and bear witness? Does not the crucified God demand that our ‘where are you?’ move beyond a desperate (or cynical) rhetorical question into a sincere inquiry, one that remembers to consider the cross?”[2]

[1] Braverman, Mark (2011, Dec. 7). What is a Kairos Document? [Presentation]. Kairos for Global Justice Encounter, Bethlehem.

[2] Jersak, Bradley (2022). Out of the embers: Faith after the great deconstruction. Whitaker House.