“Hi, Dad! It’s me…your favorite daughter.”

Sometimes I get confused. I see friends my age—empty nesters—traveling the world or earning promotions or devoting themselves to hobbies, and my excitement for them breeds a little discontent in me or even some resentment. I think—momentarily—that I am missing out. But then I remember that I could do and have all those things and more—most anything I wanted really—if I didn’t have the very extraordinary life I do have—the one I chose almost ten years ago and would choose again tomorrow…and the next day…and the next…

Unbeknownst to us, exactly ten days after we buried our son in Albert G. Horton, Jr. Memorial Veterans Cemetery in Suffolk, Virginia, a surrogate mom halfway across the country was enduring a health crisis that resulted in the premature birth of the babies she carried. I once heard it said that every adoption begins with a tragedy, and I suppose that’s one way to look at it. It may be tempting to focus on the tragedies that comprise the parallel stories of Timothy and the twins, but I prefer to focus on the eventual intersection of those stories as something extraordinary.

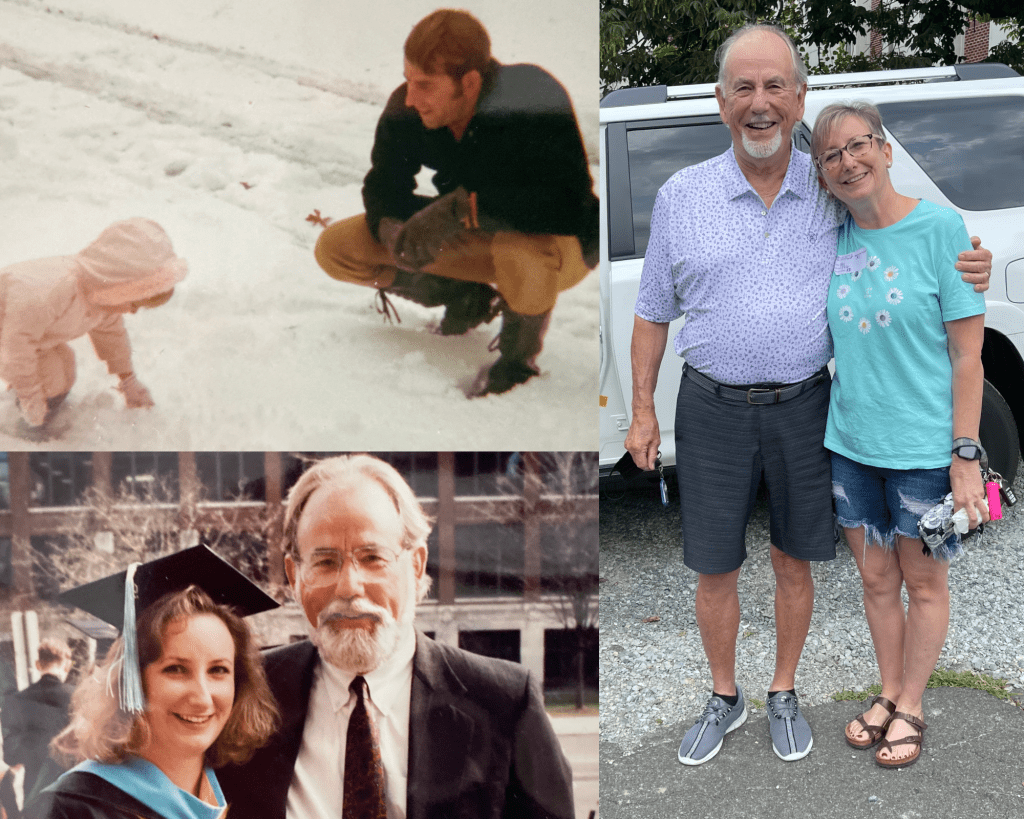

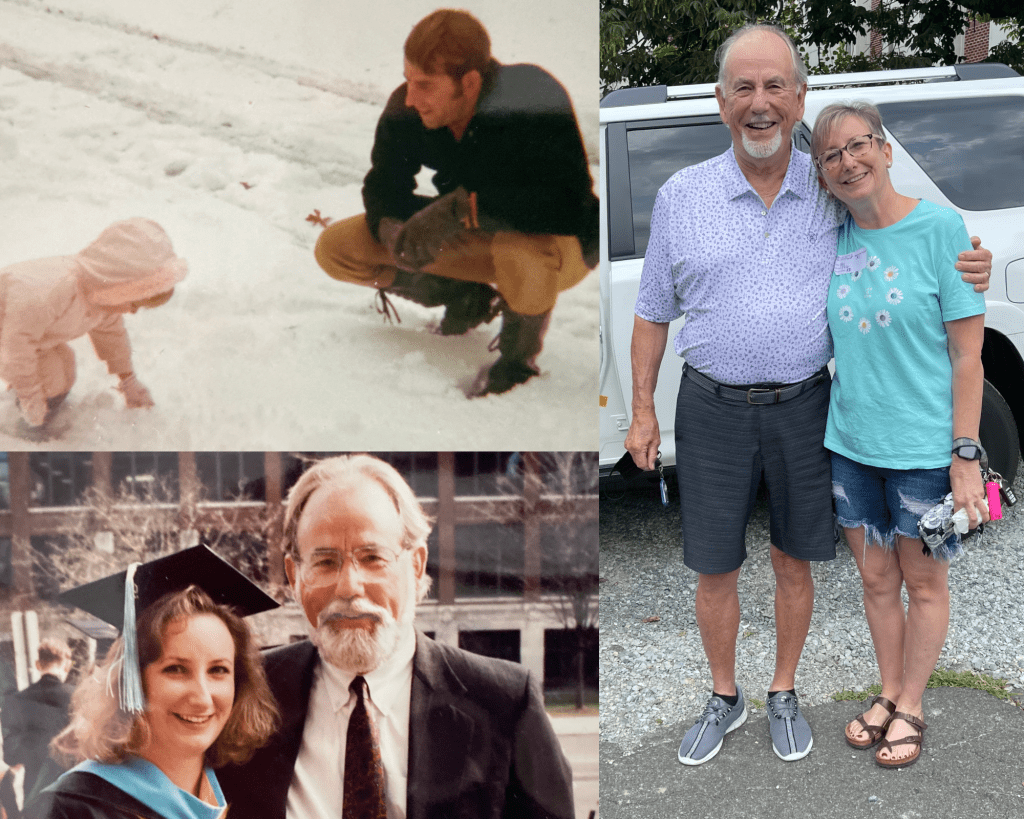

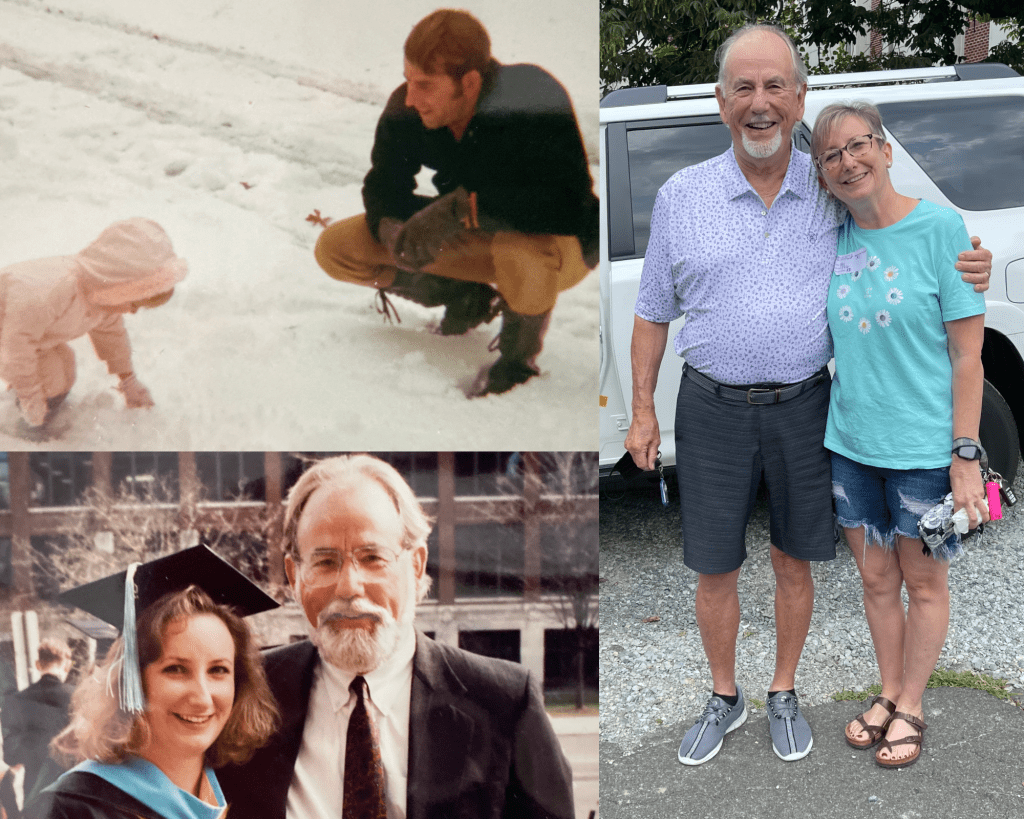

Titus and Tess celebrate their birthday today. They have lived a decade of life, and I have shared all but two months of it with them—the two months they weren’t even supposed to be out of the womb. Nothing about their lives has been easy—premature births, brain bleeds, adoption, neurodivergent challenges, divorce. An outsider watching their celebration today will see friends, family, cupcakes, pizza, a playground, some gifts, possibly some rain, and a multitude of sequins. They won’t know that Tess had 63 surgical procedures before her ninth birthday, that a doctor didn’t want to prescribe her glasses because “they wouldn’t make a difference,” or that a surgeon looked at her infant brain MRI and asked me, “Why would anyone want to adopt these babies?” They won’t know how long it took Titus to learn his colors or his letters or how agonizing it is for him to read. They won’t know how many times he has asked me why he has to have a “short memory” or a cerebral shunt that keeps him from enjoying contact sports and trampolines with neighborhood kids. They won’t know that I almost didn’t even know he existed—and that if I hadn’t known, Tess wouldn’t either.

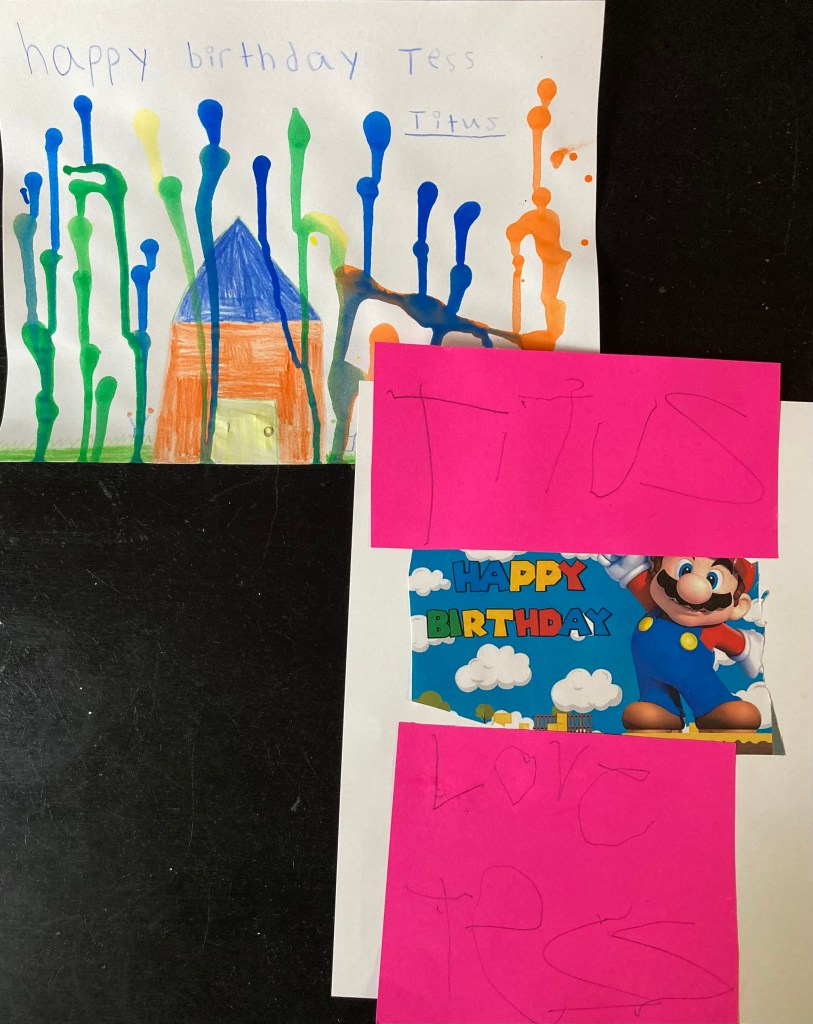

If we could play a highlight reel of this tenth year of their lives, we would see things that may look ordinary for kids of this age…a boy dancing at his brother’s wedding, acting in a play, getting baptized, playing Minecraft with his sister-in-law, solving grade-level math problems, standing at a podium reading aloud in front of a room full of people…a girl writing her name, playing piano, going under water voluntarily, reciting memorized lines in a dramatic performance, drinking water with a straw. But none of these things are the least bit ordinary. They are the culmination of hours and hours of effort that Titus and Tess put in day after day to overcome the challenges caused by the bursting of fragile blood vessels in their tiny premature brains. They are the culmination of hours and hours of diligence from care attendants, siblings, doctors, therapists, grandparents, coaches, teachers, and friends who have believed in them, challenged them, and seen potential where others saw a void. They are like the cards at the top of this post…deceptively sweet and ordinary childhood creations that represent a decade of extraordinary effort and love.

Sometimes I get confused. I am tempted to lament my lack of freedom. I think about the jobs I haven’t held, the books I haven’t written, the places I have never visited. I wonder what it would be like to take an impulse trip or even a planned vacation that doesn’t require the coordination of a multitude of people. But then I remember that anyone with time and money can do those things. My life cannot be bought or replicated. I have the privilege of witnessing the transformation of the ordinary into something extraordinary every single day.

Others may view our lives and see limitation or lack of freedom, and I suppose that’s one perspective. It can be tempting to focus on the things we cannot do—to dwell in the negative space. But like most of life, there are multiple facets to everything, and a slight tilt of the head or turn of the hand can direct the light in such a way that color bursts forth where there was only darkness before.

Ten years ago today, Esther “Tess” Moriah and Titus Asher Barnes were born emergently, a birth day fraught with crisis. Ten days earlier, a little world changer named Timothy José had gone to heaven for his healing, leaving a shocked and grief-stricken family. In the intersection of their stories, God transformed the negative void of Timothy’s death into a space in that family for a brave, strong, incredibly smart little girl and her perceptive, loving, thoughtful twin brother.

Today, I celebrate Titus and Tess’s first decade of life–a decade that has often been unpredictable, hilarious, challenging, hopeful, tragic, and joyful—but always full of love. A decade of shattering barriers, defying expectations, and overcoming adversities. A decade of countless small moments with big significance. And if you tip your head slightly and turn your hand so that the light hits the darkness, you are sure to see that it has been a decade of extraordinary.

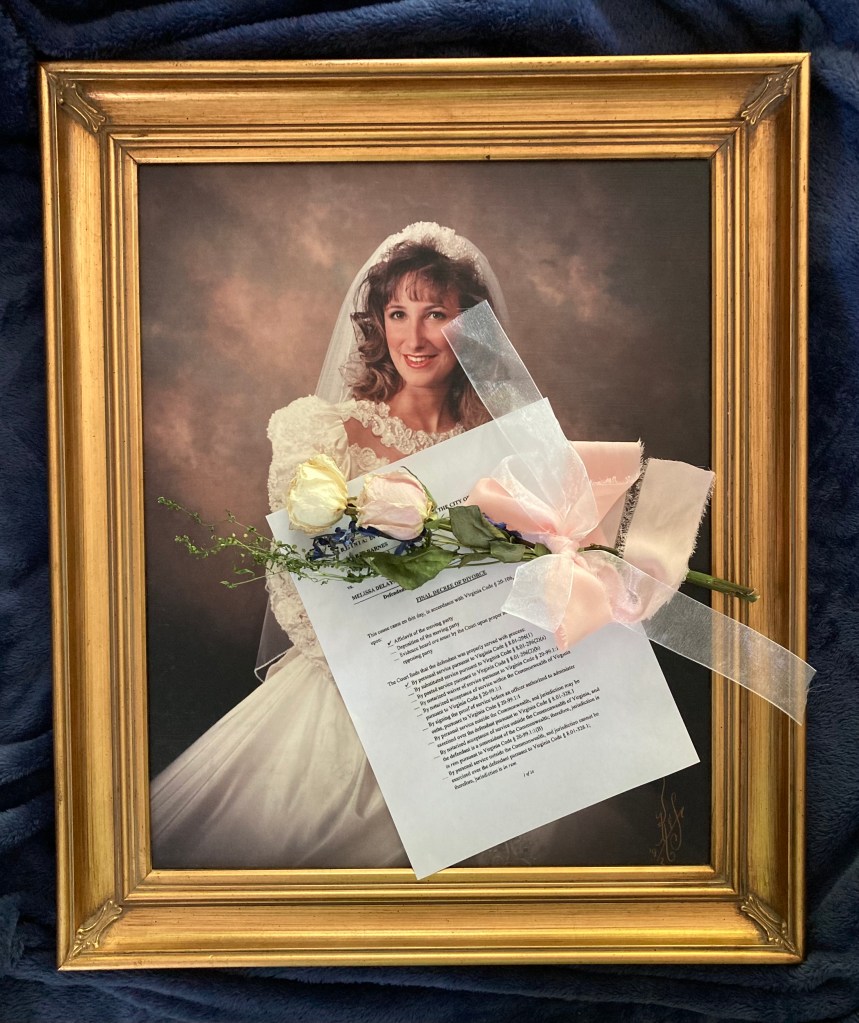

On December 4, 2017, shattered, depleted, and afraid, I filed custody and support petitions in Chesapeake Juvenile Domestic Relations Court. Though I knew they were necessary, I signed them reluctantly and with hope still in my heart for the restoration of our marriage. That hope faded over the coming months as our marital home became an increasingly unsafe space for me.

Our marriage counselor implored me to “make a safe and sane home for [my]self and [my] children,” and with the support of my family and a handful of friends-who-feel-like-family, I did that. If anyone had tried to tell me what the next few years would bring, I would not have believed them. The journey from that day to April 25, 2023—my divorce finalization day—has been both the darkest and brightest of my life. The story of these past five years, filled with delays and shenanigans, rivals the script of the most absurd soap opera. That is a story for another day. Today’s story is one of celebration.

I used to say that the failure of my marriage was the greatest tragedy of my life. I no longer believe that. Though I made an abundance of mistakes, dating all the way back to the age of fifteen, I would do it all again—even if the outcome was the same—because without that exact marriage, I would not have the family I have today. And though outsiders may view my family as broken, I see it as mended and more beautiful today than I could have imagined. The tragedy was not the mistakes that led to the marriage, its long but toxic life, or its ultimate demise but that I completely lost myself in the process. During these waiting years, I have grieved, healed, rediscovered myself, and learned what love really is. Through it all, I was carried, protected, defended, and put back together by a God I know to be utterly faithful and trustworthy.

Though I reclaimed my name at the point I realized my marriage was beyond hope of restoration, finalizing the divorce closes the circle and completes the journey of my marriage. In his book Daily Prayer with the Corrymeela Community, Pádraig Ó Tuama shared a “Prayer for a new name,” a beautiful reflection of the story of Hagar, the discarded servant who God found in her wilderness exile. She named him El-Roi, “the God who sees me.” In his prayer, Pádraig Ó Tuama wrote:

We have walked far,

and seen many things

and now,

because of what we have seen

because of where we are going

because of where we are

we give this new name now.

We do not destroy past names,

because they have brought us here.

We celebrate the new name

That will bring us on. (p. 49)

I do not celebrate my divorce, no matter how necessary it was for my survival and is for my closure, because at its root, a divorce represents the fracture of a covenant and in my case, of a family. I do not wish to destroy the memory of the marriage—even its darkest parts—because it brought me here. Instead, I choose to celebrate my journey through and out of the marriage. Those thirty years constitute what (I hope) will be at least a third of my life and cannot be separated from who I am today and will be in the future. I celebrate my survival and the ways God is putting me back together, keeping the pieces He intended and discarding the ones others imposed on me or that I acquired through my own mistakes.

I celebrate the lessons I learned these past five years—some once known but forgotten, others altogether new discoveries. I now know that I am more than a possession. I know that truth emerges in time. I realize that it is far more important to notice what people do than to believe what they say or what they say that they do. I have learned that letting my life speak is much more powerful than any verbal defense I could offer. I know that having gifts and dreams is not narcissistic but that devaluing or belittling the gifts and dreams of others may be. I know that I can change, and that it is best to walk away from a relationship with anyone who believes otherwise. I have accepted that sometimes it is more important to be saved from a marriage than for that marriage to be saved. I have learned to make every effort to avoid bitterness. I have learned that both grief and forgiveness are necessary but ongoing processes. I have learned that my purpose can be found internally—in what makes my heart sing and what breaks it—and in the exact life God gave me, not in someone or something external and elusive. And I have learned that God requires love above all else—love of Him, love of others, and by extension, love of self—a lesson I have chosen to have symbolically etched above my right ankle as a personal Ebenezer stone.

I also celebrate the people who surrounded, supported, and accepted me through all the stages of the journey—the friends and family who remained when others walked away and those temporarily blinded who returned with open eyes. I am grateful for the new friends who stepped into the mess and joined the reconstructive work. I am indebted to the counselors, pastors, and spiritual director who guided me through grief and into forgiveness and gave me tools with which to rediscover myself. Finally, I celebrate the selfless, honorable, pastoral man and his wife who sacrificed so much time and energy to advocate for justice on behalf of me and the children—a justice that is tragically elusive for most women whose life choices leave them as powerless as mine did. None of these people are named in this space, but I will always remember their names, the wisdom they shared, and how God provided for me through them.

Over time, I will share my story more fully and deeply in whatever ways God prompts and allows. I will also advocate for and encourage others who find themselves in situations like mine because that is how we make sense of our senseless stories. In the meantime, I celebrate closing the circle of my marriage—a marriage that produced the eight children that have been, and will always be, my greatest gifts and a picture of redemption to me; a marriage that revealed to me an utterly trustworthy God who fights on my behalf even when I do not understand His ways or His timing; and a marriage in which I made countless mistakes that left me shattered into pieces but that also allowed me to be remade into someone who is better for the breaking and the mending. And now that that circle is closed and celebrated, I step eagerly into new seasons, bursting with song and ready to dance!

“You did it: you changed wild lament

into whirling dance;

You ripped off my black mourning band

and decked me with wildflowers.

I’m about to burst with song;

I can’t keep quiet about you.

God, my God,

I can’t thank you enough.” (Psalm 30:11-12, The Message)

Some of my earliest memories include the sounds of basketballs…the rhythmic staccato of a dribble, the solid thump against a glass backboard, the springing vibration of a metal rim, the swish of a net. My dad took me to the junior high gym where he coached in Mecklenburg County as soon as I could walk. From there, I played hours on the asphalt cul-de-sac outside my childhood home and eventually found my way to the gymnasium where I spent the majority of my high school days, not playing but managing and scorekeeping for the Millbrook Wildcats. Every close friend and every guy I ever dated was a part of that team, and I loved every minute of it—from the daily practices to the games and everything in between. I spent hours crafting pre-game encouragement notes and treats to leave on the guys’ lockers week after week. I could sing along with all the beats that filled the air of every away-game bus ride. Rhymes by Run-D.M.C., LL Cool J, Doug E. Fresh, Kurtis Blow, and the Beastie Boys still randomly shuffle through my mind’s soundtrack.

Throughout childhood, I clipped newspaper articles chronicling every Carolina Tar Heel basketball game and carefully adhered them to the pages of magnetic photo albums. As my senior year approached, I typed a resumé and secured a letter of recommendation from our former coach, my high school mentor Chet Mebane, in pursuit of my dream of being a Carolina basketball manager. Receiving the letter from Coach Bill Guthridge notifying me that I had been accepted as a Junior Varsity manager during my freshman year at UNC was almost as exciting as receiving my acceptance letter to UNC, my lifelong dream school and the only college to which I applied.

Being a Carolina basketball manager at even the JV level was exhilarating—a ton of work and even more fun. I spent countless hours of my freshman and sophomore years in the Dean E. Smith Center. We worked all JV practices, all varsity home games, and all JV home and away games. In the summer, we served as counselors for Carolina’s Basketball Camp. I smelled of sweat, oranges, and Gatorade as I slung towels, wiped floors, chased basketballs, and handed Dixie cups of Gatorade to players—J.R. Reid, Hubert Davis, Jeff Lebo, King Rice, Scott Williams, Rick Fox, and many others. I had the privilege of sitting behind the legendary Coach Dean Smith at every home game and will never forget the time he complimented my sweater as we passed in the Dean Dome stairwell that connected the locker room level to the basketball offices.

I let my Carolina basketball manager dream die on a vine that eventually choked out several other dreams and aspects of my identity. Like many teenage girls, I invested too much effort trying to secure a very unhealthy relationship and sacrificed friends, experiences, and beliefs along the way. In the years that followed, I attended games here and there and loosely followed some of the UNC teams from afar as military moves took me out of the Tar Heel State. But mostly I forgot the girl whose blood had bled Carolina blue all of her life.

In 2021, longtime UNC Coach Roy Williams retired. When his successor was named, I did a double take. Hubert Davis was my classmate at UNC and the player I knew the best in my time as a manager. We both wrote letters in the Dean Dome bleachers to our long-distance romances and even went on double-dates when they were in town at the same time. He was hard-working, kind, and humble and I had tremendous respect for him as a freshman surrounded by big stars—stars I later learned he had gone on to outshine. Graduating from college before cell phones or email addresses even existed, I lost touch with most of my college friends. With my head in the proverbial Carolina basketball sand for three decades, I had only a general awareness that Hubert had played professional basketball and spent some time as a commentator, so I was genuinely surprised to learn he had even been an assistant to Coach Williams, much less in the running to succeed him. But I have Hubert to thank for helping me find a piece of myself that went missing for far too long.

Curious to see my former classmate coach, I began tuning into the UNC games late in the 2021-2022 season. My Carolina blue blood started pumping again as I pulled for this this come-from-behind team and its humble, faith-filled coach I respected so much even when he was just an 18-year-old freshman baller. I pulled out my 1980s Carolina newspaper clippings, dug up photos from my years of managing in high school, updated my UNC gear, and introduced my kids to the joys of being a Tar Heel. I will always remember the April 2022 night that we beat Duke in the Final Four, which was awfully close to as exhilarating as winning the NCAA title two nights later would have been (not quite, but VERY close).

This 2022-2023 season was the first time in thirty years that I have closely followed a Carolina team, watching almost every single game from start to finish. I have loved waking up on game days, choosing how the kids and I will rep the team, and timing our evening routines around timeouts so I wouldn’t miss any plays. It was a rough season that culminated in Carolina becoming the first team ranked number one in the preseason who did not even make the NCAA tournament. My heart broke for Armando Bacot and his fellow seniors and teammates who had descended from the mountain of the NCAA Finals to the valley of an NIT invitation. The social media chatter has been brutal! Seeing how fickle the “fans” can be, I made it a mission to always be the encouraging fan in the comments. We may be accustomed to success, but a true Tar Heel is loyal no matter what challenges a given team faces–the only kind of fan I want to be.

I lost so much of myself in my efforts to navigate adulthood, parenthood, and an unhealthy marriage. Over the past five years, I have slowly begun to pick up the lost pieces of myself and see how and whether they fit into my life now. I have been rediscovering loves I buried, digging up beliefs I denied, and reigniting passions I had forgotten. Part of the process has been accepting the loss of some of my dreams to broken promises and others to poor choices or my own martyrdom. Part of it has been making peace with my roles in life.

Remembering and rediscovering my passion for UNC basketball has not only been super fun but has given me a new perspective on a piece of myself. When I remember my years as a high school basketball manager, I think so fondly of the friends I made there and the times we shared. I think of how valued I felt by the coach and players as I repeatedly performed the monotonous but essential tasks of ensuring the players were hydrated, safe, and encouraged and that their efforts were accurately reflected in the scorebook. I never desired to be on the floor making the plays but thrived in my element of team caretaker and encourager.

Picking up this lost piece of myself and reflecting on it in light of today has given me a new perspective on what appears to be my life work as a caretaker and encourager. Seeing it through the lens of my past joy as a Millbrook Wildcat and UNC Tar Heel basketball manager has helped me realize that caretaking, encouraging, and managing are actually central parts of my identity—how God knit me together—not something that just happened to me or that I must resign myself to accept. I willingly chose those roles as a teenager who had the freedom to make an array of choices. I played the roles naturally and well and found them very fulfilling. The people I met in those contexts were “my people,” and I have even reconnected with some of them over the past few years. The revelation that my life today actually reflects my heart thirty years ago has brought me much-needed peace and joy.

As I watch my Heels play each game, I always notice the hard work of the managers on the sidelines. A part of me will always wonder if I would have ever made the elite Varsity Manager team. The odds were not in my favor, but I’ll never know because I walked away from the opportunity. Instead of focusing on what I can’t recover, however, I am choosing to be grateful to have rediscovered something I temporarily lost. I am having a blast sharing Carolina basketball with the people I love most in the world—my kids—just like my dad shared it with me.

I thought that when the NIT kicks off this week, I would be glued to my TV, decked out in Tar Heel gear, cheering for Leaky, Armando, Pete, Caleb, and R.J., regardless of what postseason tournament title they pursued. However, shortly after the NCAA brackets were announced, UNC Basketball released a statement saying that the team is choosing not to participate in the 2023 NIT. Coach Davis stated that “now is the time to focus on moving ahead,” a lesson I have learned well these past five years. I respect his discernment in making that choice and the wisdom of putting what his players need ahead of what may be expected. So I will pack my UNC gear away until next season when I will eagerly cheer on the next Tar Heel team. Win or lose, I won’t forget my roots again…

I’m a Tar Heel born.

I’m a Tar Heel bred.

And when I die I’ll be a Tar Heel dead.

So it’s rah rah Carolina-lina.

Rah rah Carolina-lina.

Rah rah Carolina-lina–go to hell Duke!

Welcome back, Carolina Girl. I missed you.

In April 2015, I attended Seussical, the first performance of the Arts Inclusion Company (AIC), which defines itself as a “company where people of All Abilities are welcomed to participate in all aspects of theatrical arts.” I described the experience as “a glimpse of the Kingdom on earth—a portrait of how life could be if we all risked putting our individually broken selves together to create something much more complete and meaningful than we are capable of alone.” I knew that night that when Lydia and the twins were old enough, we would join AIC. A few life interruptions and a global pandemic later, we did just that!

What I witnessed from my seat in the audience was just a taste of what we experienced as participants. From the first rehearsal to the final curtain call and every moment in between, the kids and I felt welcomed, valued, safe, and accepted. Watching the show come together over three months gave me a picture of what we can create when ego and competition and perfection are not just subdued but entirely absent.

Of all the many positive effects Lydia’s birth has had on my life, one has stood out from her very first year of life. I realized almost immediately that having a child with Down syndrome changed the way the world saw our family. Though it manifested in different ways, it was tangible. In the eyes of friends, family, and strangers, we forever lost all possibility of being a “picture-perfect family” in image and in substance. Some looked at us with pity, others with discomfort. Many just looked away altogether. Those with personal experience looked at us with understanding and joy. Some with no experience were at least curious and willing to join us on our unexpected journey.

That lost possibility for perfection transformed my life from one of pressure I did not even recognize to one of freedom. Through my children’s “dis”-abilities, I found an entirely new way to exist—one free of pressure, expectation, timelines, perfection, and pride. As Lydia grew, and with her my exposure to and appreciation for a world of people I had previously scarcely acknowledged, I began to question the dis- in disability. I would say, half joking, that perhaps it was those of us who lacked the third copy of the 21st chromosome that were actually disabled, since Lydia’s perspective and capacity for love seemed far more Christlike than most people I knew. Lennard J. Davis later gave me the academic explanation for my instinctive insight in his discussion of normalcy as a construct. Davis wrote that “the ‘problem’ is not the person with disabilities; the problem is the way that normalcy is constructed to create the ‘problem’ of the disabled person.” My transformation from a world that viewed imperfection as a problem to be avoided to one of freedom from pressure carried me through even greater “imperfections” that our family would face in the years to come.

Living free in a world dominated by pressure and expectation, however, can be very isolating and lonely at times. Society doesn’t place much value on imperfection and doesn’t know what to do with families like ours. As an (almost) single mom in communities where divorce is taboo and with only children with special needs remaining in the home, I am often the person everyone smiles at and waves to—but from afar. In an interview, Kate Bowler once shared that a common lament of individuals who have had “a big before and an after in their life” is that, “I’m everybody’s inspiration but nobody’s friend.” Being a part of AIC’s production of Peter Pan was like entering a world filled with people who live in the freedom of imperfection—a world of instant friends for me and my children. It felt like going home.

J.M. Barrie created the world of Neverland in his 1911 novel originally titled Peter and Wendy. He described the Neverlands as an invention of a child’s mind, which “keeps going round all the time,” but is “always more or less an island, with splashes of color here and there.” Barrie acknowledges that “the Neverlands vary a good deal,” with one child’s differing from another’s, but “on the whole the Neverlands have a family resemblance” and are close enough to one another to facilitate grand adventures. Neverland is a boundary-free place where limitations of reality are suspended and belief abounds. Anything is possible with a little fairy dust…even flying.

The research I conducted for my dissertation was based on the work of a psychologist named Reuven Feuerstein who believed no individual was without hope or the propensity to change. When I discovered his work, I devoured everything I could read from this man who saw potential of those society often discounted and even discarded, long before neuroscience scientifically validated his work. Feuerstein said that children with neurodevelopmental disorders such as Down syndrome can be helped and that “chromosomes do not have the last word.”

My life’s work has been to parent and educate all of my children in a way that left the world open for them to pursue whatever gifts, passions, interests, or callings God placed in their hearts. For my children who don’t fit society’s image of perfection, that has included protecting them from anyone and anything that makes them feel “less than.”

During the adventures of the Darling children in Peter Pan, Tinkerbell protects Peter by drinking his poisoned medicine. As she lays dying, Peter is only able to save her by calling on those around him to believe in fairies. From the earliest rehearsals to the final matinee, that scene resonated with me on so many levels. To live in this world, and especially to fly in it, my children need belief—belief in themselves that is protected and fanned like a flame by those around them. Sadly most spaces seek, whether deliberately or unintentionally, to extinguish that flame of belief.

Our past few months being a part of AIC allowed us to spend time in a real-world Neverland, where limitations of reality are suspended and belief abounds. I saw all ages, all races, all genders, all types of abilities come together to pool their gifts, talents, and passions to create something beautiful to offer to the world. Everything was accepted and welcomed—all that was required was a willingness to show up. Expectation, judgment, pressure, and perfection were absent. Friendship was granted simply by presence. No explanations or apologies were needed. The experience was beautiful and like Peter, I never wanted to leave.

But the final curtain closed and we returned to our everyday lives in a world that sees more limitations than possibilities—a world that doesn’t know what to do with our imperfections and brokenness. But because we know that we are not as alone as it sometimes feels, we will keep venturing out into that world so that it can begin to see all the beauty that can come from brokenness–and maybe change its understanding of “normalcy” in the process. Like Wendy, we will return to Neverland every year we are able—for a little spring cleaning and a lot of adventure. And we will keep our dreams alive in the meantime—fueled by belief…and perhaps a little fairy dust.

Five days after the murder of George Floyd, I sat by my daughter’s bed in our local children’s hospital, feeling deeply saddened and helpless about the racial division in our country. I shared a list on social media called “Anti-Racism Resources” that stated it was “intended to serve as a resource to white people and parents to deepen our anti-racism work.” Along with the link, I wrote a simple message: “Excellent list of resources for teacher friends, mom friends, and just friends in general. I want to be part of the solution.” A measly offering, I knew, but somehow it felt better than doing and saying nothing.

A Facebook “friend” that I knew only from some shared community activities over the years commented, “Though I agree with the sentiment and the drive to do something helpful, several of the resources listed in this reference have a decided political and polarizing agenda.” I was genuinely puzzled by her comment and simply responded that I appreciated a starting point for resources but trusted everyone to discern for themselves what is useful for their needs and what is not.

She was not reassured and replied with, “It’s your wall and of course you are free to do as you wish [insert happy face emoji]. I am just concerned about the widespread dissemination of anything that may be geared at creating more divisiveness.”

This exchange has stayed with me over the past several years as educational debates have raged across the country. I recently stepped away from a teaching job after being told to avoid “any politically charged issues and topics” in developing a course for teachers working with at-risk learners—a virtual impossibility, considering poverty and race are two predominant causes of a learner being at risk of academic failure. In my home state of Virginia, an executive order was passed “ending the use of inherently divisive concepts, including critical race theory, and restoring excellence in K-12 public education in the Commonwealth.” Florida just banned a new College Board pilot Advanced Placement (AP) course in African American Studies on the grounds that the course is “inexplicably contrary to Florida law and significantly lacks educational value.”

As an English teacher who has taught AP courses for the past five years, the Florida ban astonishes me. AP courses are not mandated; they are chosen by students—typically the most academically advanced students. They are carefully designed courses with rigorous guidelines because they culminate in an exam that provides students an opportunity to earn college credit. The AP courses offered by the College Board reflect an array of subject areas representative of the choices in the general education curriculum of a typical liberal arts college—Calculus, Statistics, Chemistry, Environmental Science, Psychology, Human Geography, Music Theory, European History, Chinese Language and Culture, and Microeconomics are just a sampling of the courses currently offered. A course in African American Studies is a logical addition to the AP course menu.

The statement that such a course “significantly lacks educational value” would be baffling out of the context of our current culture of stupefying political and governmental attempts to silence voices that desperately need to be heard. Ironically, the very act of avoiding “divisive concepts” perpetuates divisiveness more than the inclusion of them ever would. Rather than “protecting” students from divisiveness, these acts fracture our nation, dividing us into those who foster ignorance and those who seek understanding.

As a teacher, I encouraged my students to join academic conversations by articulating their own experiences, beliefs, and opinions and supporting them. When researching an issue, I implored them to go first to primary sources—the letters, speeches, transcripts, and memoirs of participants in whatever historical, scientific, or cultural event they were studying. If participants were silent, I encouraged them to discover why. Were they illiterate? If so, why? Did a disability or lack of access to necessary tools inhibit their ability to communicate their experiences? Did systems exist that silenced or simply did not value their perspectives?

Primary sources are not infallible. History is not definitive. Perspective and context are vital components of every story. The same experience told from multiple viewpoints will always sound different, much as each instrument in an orchestra produces a unique sound and plays a unique part of a movement. Diverse, even contradictory, stories paint a fuller, more detailed picture of an event and while they can never fully capture an experience, they provide a curious individual the opportunity to at least try to understand the event or situation being described. Omitting the most tragic, flawed, disturbing parts of a history deprives a learner not only of the full picture but also of the lessons to be learned, even from failures and atrocities. The authors of the Old Testament books of Judges, the Kings, and the Chronicles clearly knew this.

I, too, once thought that the goal was to ignore difference and pursue unity. But unity doesn’t require sameness or turning a blind eye to difference. The foundation of unity is a common respect for the value of human life—every human life. Understanding as much as possible about the histories and experiences of others is unifying, not divisive. My experience as a white single parent of children with disabilities differs from those of my black friend who parents two young adults, including a son, in a culture where black men are in danger if they are pulled over for a burned-out taillight. They differ from those of a friend who co-parents her son with her fiancé, her ex-husband, and her ex-husband’s husband. They differ from a Sikh family that is torn between the desire to pass on tradition and the risk of sending a turbaned man out into a world of fear and hate. They differ from the men and women who sit on death row either because they made a mistake or because someone else did and they were falsely imprisoned for it. They differ from a child who grows up in a neighborhood where drugs are easier to get than food. They differ from my own child whose brain suffered so much damage at birth that she struggles to see, to eat, and to move her body in the simplest of ways. I will never fully comprehend any more than someone else could fully grasp my lived experience, but every story I hear or read expands my capacity for empathy and my sense of unity to the people in our beautifully diverse nation.

My own journey to understand more about racial justice has shown me both the impossibility of truly understanding and the necessity of never ceasing my efforts to do so. In the weeks after George Floyd’s murder, I had the opportunity to participate in a prayer march with members of my church. I have never felt more truly a part of the body of Christ than I did marching through the streets of Norfolk, Virginia, with my Black Lives Matter sign. But I was also taken to school that day. Listening to community leaders speak about specifics of systemic racism in our community opened my eyes to how very little I know about how we got to where we are today. I am an educated person. I am a teacher. I have had many black friends through all stages of my life. I admire numerous black heroes in our nation. I took college courses on African American literature and have included works by Frederick Douglass, Martin Luther King, Jr., James Baldwin, Malcolm X, Maya Angelou, Bryan Stevenson, and many other black writers in my English courses for years. I thought, at the very least, I was not part of the problem. But after listening to speaker after speaker at that prayer march, I realized how incredibly ignorant I have been to the depths and sources and consequences of the racial disparities in our nation and how complicit I am in them.

Since that June day in 2020, I have read and listened voraciously, trying to learn what my education failed to teach me. I have been a student of Anthony Ray Hinton, Jr., Esau McCaulley, Wes Moore, Ian Manuel, Austin Channing Brown, Brandon P. Fleming, Howard Thurman, Nikole-Hannah Jones, Danté Stewart, Ibram X. Kendi, Cole Arthur Riley, and Derrick Bell. My bookshelves overflow with the stories and perspectives that will teach me next. Everything I read or hear simultaneously helps me understand more and highlights the fact that I can never truly understand. It exposes not only my ignorance but also my illusions of innocence. As long as the problem of racial injustice exists, we are all part of the problem. Every story I hear has expanded both my understanding of the “faces at the bottom of the well” and my desire to join their ascent, however hopeless it sometimes feels.

The idea that a course in African American Studies “significantly lacks educational value” is ludicrous. It would be valuable for every American citizen to take that course—and a course on every other marginalized people group in our country for that matter. We all need MORE understanding, not less. The word educate is derived from the Latin root educat (led out). To educate is to lead someone out of ignorance, not by deciding what they should know or believe but by equipping them to be critical thinkers who are capable of reading multiple perspectives, discerning their own understanding and beliefs, and then adding their voice to the conversation—the conversation of a diverse nation united by its mutual respect for the people that comprise it. The thought of any individual seeking to hinder another individual’s access to specific perspectives and stories defies the very purpose of education. It is an act rooted in ignorance and fear. It is the epitome of the very divisiveness it seeks to eradicate.

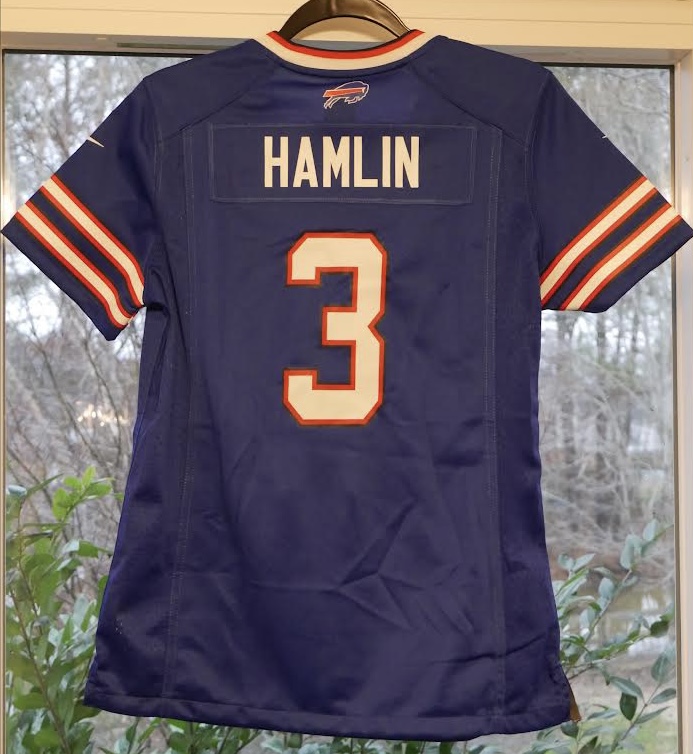

I ordered my first official NFL jersey last week. It only took me 52 years. I enjoy a good pro football game but have never closely followed an NFL team. My team loyalties lie with my college alma maters. As a lifelong UNC Tar Heel basketball fan and a dedicated Michigan Wolverine football fan, I bleed Carolina blue on the basketball court and have Go Blue forever imprinted in my DNA from grad school days in “The Big House.”

I will wear my Buffalo Bills Hamlin 3 jersey with no pretense of being a member of the Bills Mafia (yet) but simply as a grateful tribute to the hope and inspiration I witnessed over the first week of 2023. In stark contrast to the embarrassing fiasco played out in our nation’s capitol by bickering national “leaders,” watching the events surrounding Damar Hamlin’s traumatic injury unfold exemplified all the good I want to believe about humanity and our nation’s potential.

I once longed for Condoleezza Rice to run for president and think I now understand why she set her sights on the NFL commissioner position instead. Two decades ago in the New York Times, Rice was quoted as saying, “I think it would be a very interesting job because I actually think football, with all due respect to baseball, is a kind of national pastime that brings people together across social lines, across racial lines. And I think it’s an important American institution.”

That’s exactly what we witnessed over the first week of 2023 and it was truly beautiful. Hamlin’s injury was horrific and terrifying, and I wish it had not happened to him. But all that was triggered the moment he crumpled to the turf was extraordinary and will hopefully carry him through his long road to recovery and beyond.

When I wear my jersey, I will think of Damar’s parents, who hospital personnel and the Bills head coach described as exemplary in their handling of their son’s life-threatening injury. As a parent of multiple children with complex medical issues, I have spent many days of my life in ICUs, including the day our son Timothy died there. It is both an overwhelming and beautiful place to be, but it is not an easy place to be. Tensions run high in life-or-death situations, and the ICU is a constant life-or-death situation for its inhabitants. The ICU staff is trained for that, the patients are fighting for their lives, but family members are thrust into the environment, usually without warning. Sleep is elusive, stress abounds, and the stakes are high. To have your parenting described as exemplary in that context is an impressive tribute.

Damar credits the presence of his parents as “the biggest difference” in his life, but that presence did not come easily. Damar’s dad was imprisoned for a drug conviction for three-and-a-half years of Damar’s childhood. Whatever choices may have led to Mario Hamlin’s conviction as a young father, they were clearly overshadowed by his choice not to let that define him or give him an excuse to abandon his son. As Bryan Stevenson of the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) says repeatedly, “Each of us is more than the worst thing we have ever done.” The fact that Nina and Mario Hamlin held their young family together through such adversity likely prepared them for what they faced on January 2 and the days that followed; the hottest fires forge the strongest steel. When I wear my jersey, I will hope to parent my family with the same resolve.

My Tar Heel legacy (born, bred, dead as our fight song so eloquently states) imprinted me with a clear understanding of rivalry and competition. When we beat Duke in the semifinal game of the 2022 Final Four, that was as satisfying to me as winning the national title would have been. (In addition to passing the dreaded swim test, all UNC grads are mandated to hate Duke for the rest of their days.) Seeing the intensity of the Bengals-Bills competition immediately dissolve into unity in prayer and support for Damar on the field and over the week that followed was incredible to witness. Cincinnati’s acts of hospitality and support trickled across the nation and into Week 18 of competition as opposing players, coaches, and fans expressed support for Damar and the Bills. When I wear my jersey, I will carry these memories as hope for our polarized nation.

Medical providers have long been heroes in my world. The heart surgeon who repaired the hole in my daughter’s heart and the perfusionist who simulated her heart and lungs while the surgeon worked seemed to have superpowers in my eyes. The many nurses, doctors, respiratory therapists, and countless other medical providers who have cared for my kids year after year have my utmost respect. Seeing the athletic trainers, paramedics, trauma physicians, and other “ordinary” folks doing their everyday jobs while the nation was riveted to television broadcasts and Twitter updates allowed a dark situation to illuminate something that happens somewhere every single hour of every single day. When I wear my jersey, I will remember the people who live ever-ready to fight for the life of whoever needs their care.

My youngest son is my sports-watching buddy, but he can never play a contact sport because of the cerebral shunt placed in his head just before his first birthday. He can’t emulate the physical prowess of the elite athletes we cheer for, but I will surely encourage him to show the love and brotherhood that Damar Hamlin’s NFL brothers demonstrated this past week. The hugs, tears, and prayers were not limited to the minutes or even hours that followed Damar’s cardiac arrest but extended into the next weekend and to the week of his return to Buffalo. In a world where masculinity is too often equated with self-reliance, bravado, and emotional absence, we sure needed to see that when shaken by sudden trauma, the biggest, strongest, toughest men in our society dropped to their knees, bowed their heads, and pleaded for the life of their brother. And as they waited days for news, they clung to and took care of each other. When I wear my jersey, I will remember that as Damar tweeted after waking up to find he had “won the game of life,” “Putting love into the world comes back 3xs as much.”

I do not subscribe to the philosophy that tragedies happen “for a reason,” but looking for the good and the hope in darkness has served me well in the hardest seasons of my life. Damar Hamlin has a long recovery ahead of him, but everything I have seen from him, his family, and his teammates makes me believe that they, too, will be looking for the good and the hope. Perhaps the nation that came together in the first week of 2023 to show “Love for Damar” can put some love back into the world by believing that young dads in prison can grow into exemplary parents and by supporting overworked medical providers whether they care for pro athletes or kids with disabilities. Maybe we can encourage our sons to look up to men who pray and cry and hug and stand in unity, even for their “enemies.” And perhaps our polarized nation, whose leaders seem to be constantly embroiled in conflict, can follow the NFL’s playbook this past week and come together across racial, social, and political lines. That’s the team I want to be on—the team whose jersey says Hamlin 3.

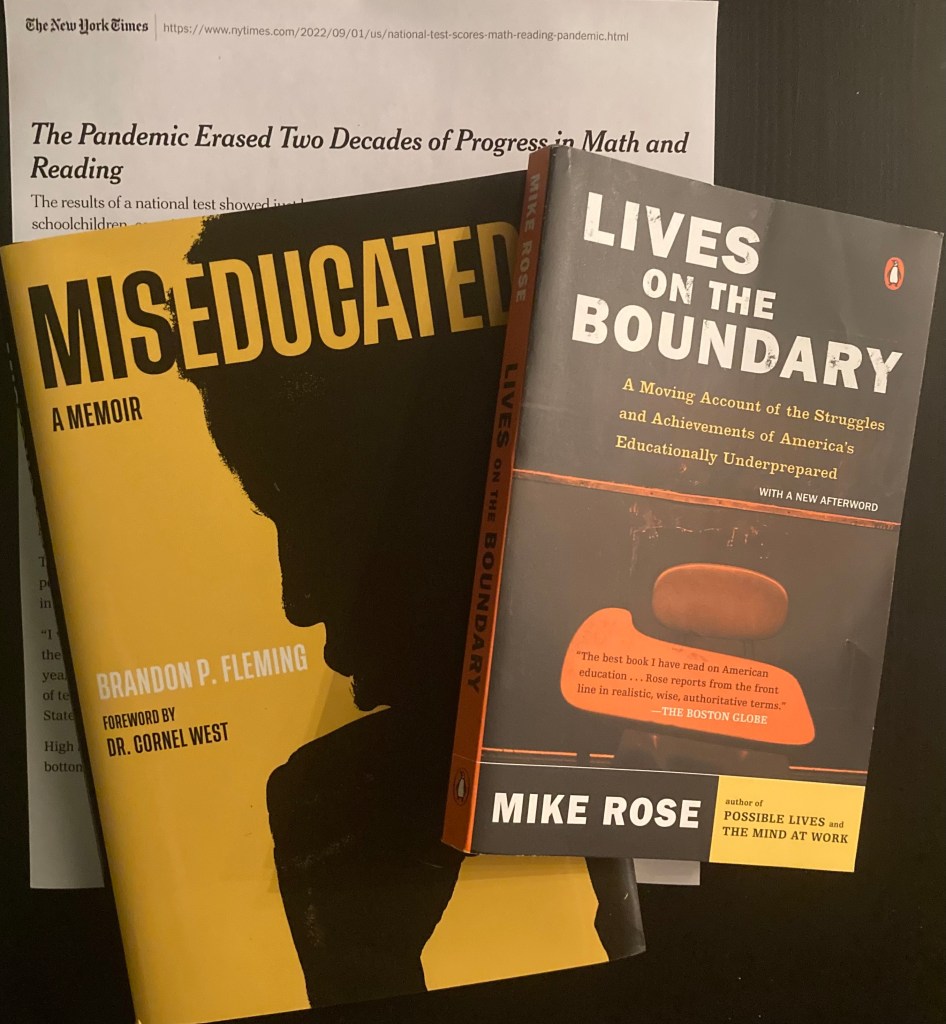

The New York Times headline that splashed across our devices three weeks ago screamed The Pandemic Erased Two Decades of Progress in Math and Reading. It’s time for American educators to scream back.

Did the pandemic erase two decades of progress? No. Did it harm our youth in a myriad of ways? Yes. But the data that prompted the screaming headlines don’t capture the harm. They capture the results of a national sample of nine-year-olds on a standardized test. Once again, a snapshot from an isolated instrument is used to make a broad statement about systems and individuals, neither of which it can remotely encapsulate. The broken state of education in our nation goes much deeper than a standardized test can possibly depict, just as the learning potential of the student taking that test is so much more than it can possibly portray.

I have been an educator since the day I knew what one was—from the tiny schoolroom my parents let me create in our spare bedroom to teach my animate and inanimate pupils (aka my brother, my grandmother, and my stuffed animals) to a wide variety of classrooms over the past thirty years, ranging from a rural high school in North Carolina to an inner city junior high in Florida to a graduate classroom in Michigan to an alternative high school in northern Virginia. I have taught online, in people’s homes, in church classrooms, and on my living room couch. I have worked with AP students who earned perfect scores on the SAT and students who have “no measurable IQ.” The study and practice of education has been my life’s work.

And that headline makes me want to scream.

The alarm sounded by the “nation’s report card” will be received as the educational equivalent of a six-alarm fire to which all available personnel should respond. But if the response is federal policies crafted by polarized politicians to pour funding and programs onto the fires of our educational system that will be deemed successful when the standardized test scores of nine-year-olds rise from the ashes and show that pandemic losses have been regained, nothing will have changed.

American educators, it is time for us to scream back at the headlines. If you interact with a child in our nation, you ARE an American educator. Our global, interconnected, fast-paced world is the classroom of our nation’s youth, and the most educationally valuable moments of a child’s day are any in which he or she is engaged in everyday life with another human being. Our children’s education IS in crisis, but the problems are much bigger than a standardized test can possibly capture. Our youth live technology-saturated lives and face unbelievable risks of violence, addiction, and abuse. Our teachers have an innate passion for teaching and a love of young people but have been shackled for years by standards, tests, policies, and paperwork. Parents are overwhelmed, overworked, and under-supported in their day-to-day lives. And our leaders are embroiled in an unbelievable national display of pervasive, ego-driven polarization in which everyone loses.

Almost thirty years ago as an eager graduate student in the University of Michigan’s School of Education, I devoured the words of Mike Rose in his autobiography Lives on the Boundary. As Rose reflected, his story “makes particular and palpable the feeling of struggling in school, of not getting it, of feeling out of place” but also conveys “an overall narrative of possibility, possibility actualized through one’s own perseverance and wit, yes, but also through certain kinds of instruction and assumptions about cognition, through meaningful relationships with adults, through a particular set of understandings about learning and the relationship of learning to one’s circumstances” (p. 247). His work guided and inspired my classrooms for years to follow.

A few weeks ago as I drove to visit my father, I was equally mesmerized by the voice of Brandon P. Fleming as he narrated his memoir Miseducated. Fleming’s story is remarkable and profound and inspiring. It simultaneously encapsulates the despair and the hope of what education is and what it can be. His vision and his commitment to act on that vision dramatically changed the lives of numerous young people and their families—not to mention his own. In the epilogue of his memoir, Fleming implored his scholars to use the voice he helped them discover to break barriers and shift balances of power. Fleming reflected that “where a man has no voice, he does not exist. He can even be present and not exist, because inferiority is an induced consciousness whose physical manifestation begins with silence. He is seen, but he is not heard. He is not understood. Because he does not matter…But when he discovers his voice, he determines that he can sing and summon the sound of hope” (p. 251). By singing his own song, Fleming inspired me to sing mine.

Rose and Fleming, two men who lived in very different times and cultures affirmed the same truth I captured in my dissertation written this past year—a study based on the theories of Reuven Feuerstein that captured the powerful mediation of mothers homeschooling learners with special educational needs and disabilities. It is the truth that beats in the heart of every educator and must be the central tenet for any person or program that hopes to facilitate true learning. That truth is the belief that every single individual has something to offer and the potential to learn and grow—EVERY individual—from the nonverbal, non-ambulatory son of one of my dear friends to the high school student with the perfect SAT score to the adolescent gang member in the prison cell awaiting trial as an adult to the little girl with the “immeasurable IQ” who wakes up in my house every morning eager to learn. To learn and grow and discover what they have to offer, they need people to see them, love them, invest in them, and equip them. They need their basic needs met. They need to feel safe. They need assessments that measure their learning propensity and education that is tailored for them, not standardized education geared toward standardized testing of standardized “learning.”

The alarm has sounded on a national crisis in education that is not two years but many decades in the making. Its solutions will not be found in polarized, politicized, bureaucratized systems but in the individualized education of unique students with unique needs. It will take place in homes, classrooms, fields, studios, workplaces, and communities across the nation. It won’t look the same for every child because no child is the same as another. It will require innovations like those of educators like Rose and Fleming and the mothers who shared their stories with me. Most critically, it will demand trust—not in politicians or policies but in people—traditional and nontraditional teachers—and the young people they are inspired to teach. It will require advocacy and a willingness to listen. It will require leaders to set aside egos and personal agendas and provide what is needed to make a difference in individual lives and communities. It will require teachers, students, and parents to “sing their song” and to listen to the song of others. Some of those songs will be beautiful and inspiring; others will be tragic and painful to hear. We will learn from them all and if we act, lives will change—one at a time—and with them, our nation.

American educators, it’s time to scream back.

The violent attack on Salman Rushdie troubled me on multiple levels. Previously, I only knew of him from media reports I read about following the controversial publication of The Satanic Verses. Realizing the threat he has lived under for decades because of ideas he had and words he penned and that he now has “life-altering injuries” as a result of his willingness to stand on a stage intended to provide a safe space for persecuted voices, is both humbling and terrifying.

Sadly, it is not a new story.

I think of Bryan Stevenson enduring countless threats against his life to write on behalf of justice for the incarcerated. In his memoir Just Mercy, Stevenson described one of the numerous bomb threats his office received, “After we cleared the building, the police went through the office with dogs. No bomb was found, and when the building didn’t blow up in an hour and a half, we all filed back inside. We had work to do” (p. 204). Despite the threats, Stevenson has devoted his life to a call to “[b]eat the drum for justice” (p. 46).

I consider Valarie Kaur as an undergrad driving across the country in the days immediately following the September 11 terrorist attacks, bravely capturing the stories of the violent hate crimes inflicted on Sikh Americans, Christian Arabs, South Asian Hindus, and Black Muslims. She reflected in her memoir See No Stranger, “I didn’t understand it then, but recording the stories was secondary to our real work—grieving together” (p. 43).

I recall Frederick Douglass risking his life to acquire literacy and then continuing to risk it to educate and inform his fellow slaves. Not only did his courage lead to freedom, but in taking the further risk to publish his narrative, Douglass continues to enlighten those of us who desperately need a glimpse of the atrocities of slavery in order to understand our own times.

As a writer and a writing teacher, I think about words constantly. I’m the rare soul who punctuates her texts and re-reads her emails five times before sending them to be sure they say exactly what I intend. Even then, there is plenty of room for “error,” as written communication is a reciprocal process between a writer and her reader. Each brings her own experiences and understanding to the text, creating a beautiful symbiosis where meaning is constructed not imparted.

Our culture allows for the instant sharing of ideas on very public platforms, such a difference from the context in which Rushdie first garnered such outrage. This makes the work of a writer that much riskier. Now we are immediately banned, cancelled, labeled, and attacked in a myriad of ways for sharing our thoughts and our stories.

However, the greatest risk is to the individual banning, cancelling, labeling, and attacking others, for a closed mind is a dark, lonely, and dangerous place. We cannot be afraid to read and hear the stories of those with whom we disagree. We cannot silence people because we don’t understand them or their experiences. And we cannot let those who are afraid of our truths keep us from writing or speaking them.

I remember soon after the murder of George Floyd, I shared a list of resources related to racial justice on my Facebook page. A “friend” suggested I remove it because of the potentially inflammatory nature of some of the texts on the list. I politely declined, thinking that fear of reading someone else’s truth is a tremendous hindrance to the understanding and healing our nation so desperately needs. The confirmation hearings of Ketanji Brown Jackson and the educational debates about critical race theory evoked similar feelings of puzzlement and dismay in me. Why would I be afraid for my children to read and hear multiple perspectives? It is honestly more terrifying to think of them growing up with a narrow, one-sided view of the world.

Just as we must all have the courage to write and speak our stories, we must be equally eager to listen as others share their experiences in trustworthy spaces such as those encouraged by Parker Palmer and The Center for Courage and Renewal. In Palmer’s circles of trust, the philosophical underpinning is that “each of us has a voice of truth within ourselves that we need to learn to pay attention to.” The safe spaces created by establishing “a few basic operating principles” that include “no fixing, no saving, no advising, and no correcting each other” allows a place for individuals to be “alone together or in solitude in community” where “anyone can say anything they regard as true into the circle” (The Greg McKeown Podcast, Season 2 Episode 17).

As Kaur wrote, “Deep listening is an act of surrender. We risk being changed by what we hear. When I really want to hear another person’s story, I try to leave my preconceptions at the door and draw close to their telling” (p. 143).

Stevenson has been driven by a similar philosophy influenced by his grandmother, the daughter of Virginia slaves, who constantly told him, “You can’t understand most of the important things from a distance, Bryan. You have to get close.” He has devoted his life to maintaining “[p]roximity to the condemned, to people unfairly judged” and to righting “the injustice we create when we allow fear, anger, and distance to shape the way we treat the most vulnerable among us” (p. 14).

Kaur went on to acknowledge the difficulty of listening to someone whose beliefs are abhorrent, enraging, or terrifying to you. She concluded that, “In these moments, we can choose to remember that the goal of listening is not to feel empathy for our opponents, or validate their ideas, or even change their mind in the moment. Our goal is to understand them” (p. 156).

My personal experiences with this pale to those of Rushdie, Stevenson, or others whose very lives are at risk from the words they write. But I share their conviction that the risk only intensifies the importance of their work.

Now in the second “half” of my life, I am relishing the immunity articulated by Richard Rohr who recognized that in this “second half of life, people have less power to infatuate you, but they also have much less power to control you or hurt you. It is the freedom of the second half of life not to need” (Falling Upward, p. 157-158).

I will always write in support of justice and in opposition to oppression. I will speak out against abuse and racism and sexism and white supremacy. I will advocate for those individuals that society often doesn’t see or hear. I will be the girl in the pew speaking up for love when it seems that judgment often dominates. And I will have the courage to share MY story, MY thoughts, MY experiences, and MY attempts at understanding them. Because no one else can do that for me, and to give in to fear of judgment, criticism, conflict, or cancellation is to give up freedom. As New York Governor Kathy Hochul said after the vicious attack on Rushdie, “I want it out there that a man with a knife cannot silence a man with a pen.”

So as an oppressed Disney princess once belted: “I won’t be silenced. You can’t keep me quiet–won’t tremble when you try it. All I know is I won’t go speechless.”

I squinted uncertainly at the light peering in through my daughter’s window, struggling to clear the fog of a too short sleep. Beneath the fog laid an awareness that I was in that precarious space between. One year had ended just before I fell asleep, and I had awakened to another. As Lucy pushed back the coats of the wardrobe and stepped onto the crunchy snow of Narnia, I greeted 2022 with curiosity: Will you be as bizarre as your two older siblings in the second decade of the 21st century? What unimaginable losses and gains will we tally to you a year from now? Will I graduate this year? Will I find the fortitude to launch another adult child, knowing the crater that will leave in my days? What new barriers will my youngest children break? Will I finally be divorced this year, or will I “celebrate” thirty years of marriage marriage in May? Will this year be a year of healing for the father I am certain I cannot live without? What books will I read, words will I write, songs will I sing off-key? Where will I travel? Who will I meet? Where and how will God meet me?

I am surprised by how comfortable the space between has become. For so long I tried to control it, rush through it, or fight it. It was too uncertain, too anticipatory, too unknown. It is still those things, so it must be me who has changed—or more likely, me who has been changed. In so many ways I have learned to live in a perpetual space between; perhaps that was the only way I could begin to tolerate ambiguity—to learn to trust. For so long, I planted my feet on shifting unstable structures and expected them to hold me up.

I made so many of my life’s greatest mistakes in an effort to squirm out of the discomfort of the space between—so uncomfortable living with heartbreak or loneliness that I was willing to close my eyes and put my fingers in my ears while marching further into unhealthy situations because turning to the right or left—or worse, going backward—seemed unbearable. The toxic familiar becomes deceptively safe.

Some of the spaces between seem unbearably difficult—infertility, a terminal diagnosis, a catastrophic injury. I recently read and was forever changed by the memoir of Anthony Ray Hinton, an innocent man who spent thirty years on death row. In reflecting on a turning point in his unjust, inhumane incarceration, Hinton wrote: “…I realized that the State of Alabama could steal my future and my freedom, but they couldn’t steal my soul or my humanity. And they most certainly couldn’t steal my sense of humor. I missed my family. I missed Lester. But sometimes you have to make family where you find family, or you die in isolation. I wasn’t ready to die. I wasn’t going to make it that easy on them. I was going to find another way to do my time. Whatever time I had left. Everything, I realized, is a choice. And spending your days waiting to die is no way to live” (The Sun Does Shine, p. 118).

Hinton’s situation was truly unimaginable. He lived in a horrifically unjust space between—a space between justice and injustice, between truth and a lie, between imprisonment and freedom—and until the Equal Justice Initiative become involved in his case, he had no tangible hope to leave that space. Even when Bryan Stevenson agreed to represent Hinton, the space between extended for twenty-six more years—far too many. Reading how Hinton used his space between to learn and serve and love and forgive will forever be one of the most inspirational experiences in my life. Hinton made those choices with absolutely no guarantee that his space between would not dissolve into his final space.

Ultimately, isn’t all of life the space between? Not of this world, my heart longs for eternity; however, recognizing this does not mean living in constant limbo or uncertainty, for unlike the space between of the days and years of life, eternity has a seemingly contradictory concreteness about it—being both incomprehensible and utterly safe because the God who promised it is both mystery and certainty.

Sure, there are inherent restrictions in my space between. Until I graduate, I cannot write or teach as a PhD—at least not in any formal capacity. Without the closure of divorce, I cannot seek another relationship—at least not a healthy one in which I have a truly free, truly whole, truly healed self to offer another. I have learned to anticipate those events with an expectancy rather than an urgency—exploring the space between instead of trying to deny it or fill it prematurely.

Now it is July and this year is half over—I did celebrate my 30th wedding anniversary with a glorious (and borderline scandalous) trip to New York City in honor of my daughter and her best friend’s high school graduations. I was unexpectedly whisked off my feet by the infamous Naked Cowboy who serenaded me in Times Square with a slightly crass anniversary song. I saw all but one of the original cast members in Hadestown, an incredibly thought-provoking show that is also about the space between, in its own way. And then I came home, got COVID, healed, finished my dissertation, and lost my teaching job for next year due to lack of enrollment in this crazy economy.

So much is still unknown about this year—I might graduate, my divorce might finally be finalized, I might find a new job. Perhaps another cowboy will whisk me off my feet? Beyond that, who knows? When I submitted my complete dissertation draft, a friend asked if I felt light as a feather. I told her “Not yet. I feel like I gave birth to a baby who is in the NICU and I’m not sure how long it will be there.” But that doesn’t scare me like it used to—this space between. It forces me to trust, makes me comfortable with mystery, and keeps me from thinking I am in control—vital components of a life of faith in a God who reveals Himself but not necessarily His plan. The only life for me.